Ontario's Tuesday tornado outbreak was an 'airborne octopus’

On Tuesday, Sept. 7, a large tornado touched down in Huron-Bruce, leaving a path of destruction in its wake. The Weather Network storm chaser and meteorologist, Mark Robinson, was on the scene and captured the moment the 'complex' supercell began showing signs of rotation. He takes us through his spine-chilling experience where he not only found himself alongside — but inside — the core of the storm.

To my right, the cloud had taken on a greenish blue tint, a signal that tremendous amounts of ice were falling through the precipitation core.

Huge funnels swirled down from the edge of the core and for a moment, I thought to myself, “This thing looks like an airborne octopus. A gigantic, airborne octopus that is going to remove my car from the road if I don’t stop!”

What I was seeing then was something more akin to an Oklahoma storm, not an Ontario one, and especially not one in September. That’s when I realized I wasn’t looking at just a storm core full of hail. I was looking at one of the largest tornadoes I’d ever seen in Ontario.

And I was driving right into it…

On Tuesday, Sept. 7, the atmosphere was primed to produce severe thunderstorms and while tornadoes were possible, they weren’t likely to be violent supercell ones. We were anticipating what we call Quasi Linear Convective System (QLCS) spin ups – small, relatively weak tornadoes that get going along the front of a long line of thunderstorms.

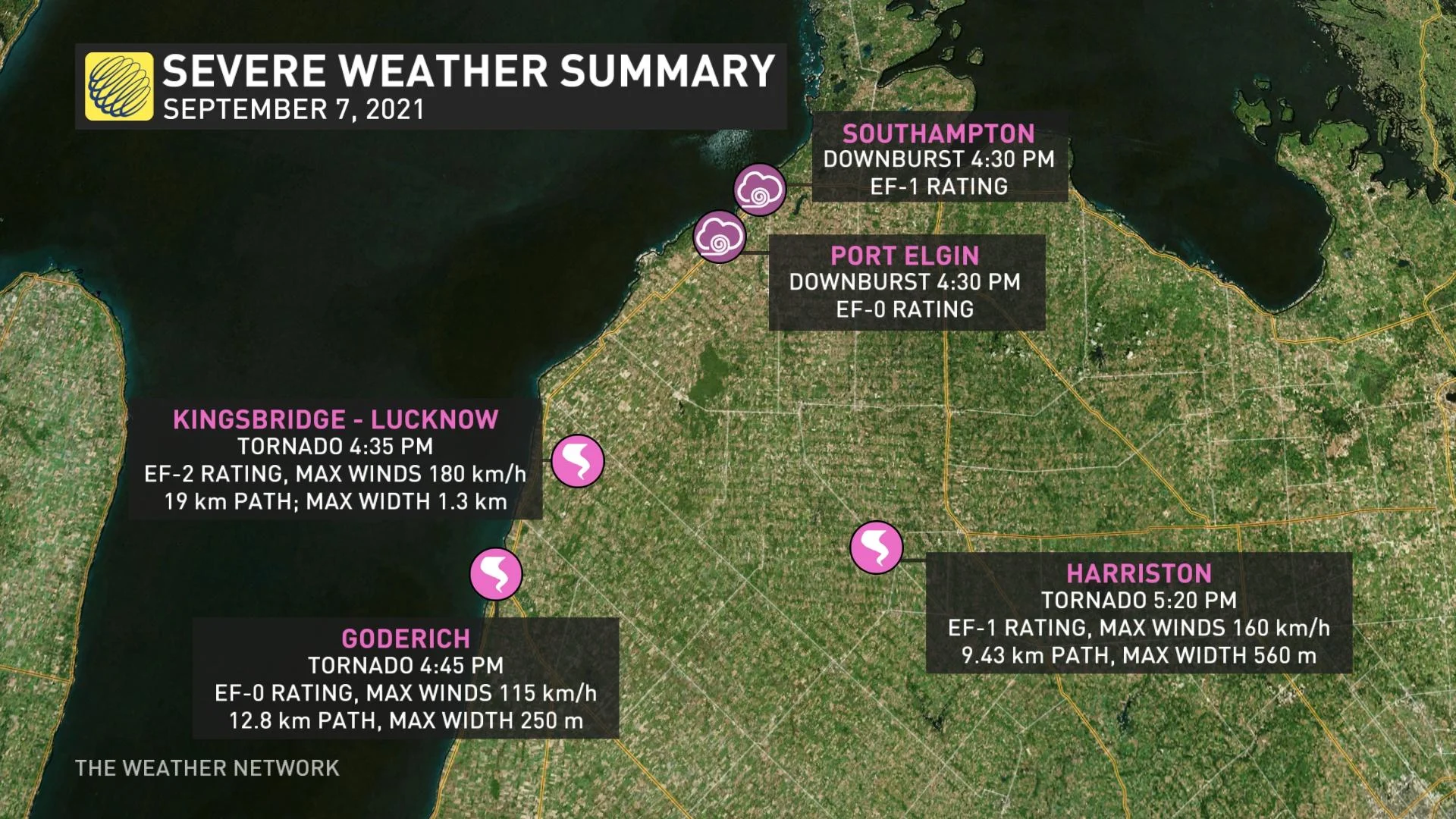

In the end, the Northern Tornadoes Project would confirm these storms produced three tornadoes and two downbursts.

Late season thunderstorms don’t usually have a lot of heat to work with, but the dynamics of the atmosphere (the speed and direction of air motion), are often very powerful. On the 7th, those dynamics pointed to a strong line of storms with resulting downbursts and possible wind damage. The big issue was timing. If the line came in at, or just after dark, it would have almost no energy and would be weak. If it came in early, the energy available would supercharge the line and result in a significant damage day.

I headed up to Point Clark, just south of Kincardine, a bit early because I wanted to have a chance to be in place and not be running around frantically at the last second. As I was passing Elmira on my way north, I stopped to check radar and realized that things were happening far earlier than I’d originally forecast. The line was already over Huron and heading south fast.

I arrived at my target of Point Clark as the line began to loom out of the haze to the north. I joined the other chasers on the wall of rocks in the harbour and in only a few minutes, the line swept into full view. And, only a few moments later, one of them yelled “Tornado! To the south!”

My first glimpse of it was a thin, white tube extending from the cloud base to the surface of the water. Behind it, a dark mass seemed to be lurking in the shadows cast by the storm above, but I couldn’t be sure. We filmed it for a few minutes and just as the shelf swept over us, we made a run for the cars and headed south out of Point Clark to intercept the tornado.

Trying to understand what was happening in the heat of the moment was near impossible, but in the aftermath, I talked to Dr. David Sills, the head of the Northern Tornadoes Project, about the storm. He explained that the tornado formed from a supercell that had been created by the collision of a cluster of storms over Lake Huron that had been overtaken by the main line that we’d expected to see. As it did, a monster supercell was born over the warm waters of the lake and within, a massive, unusual tornado.

Tornado captured over Lake Huron on September 7, 2021. (Mark Robinson/The Weather Network)

What I didn’t know was that the evolving tornado was one of the most complex ones I’d ever seen. Dr Sills found that the main circulation of the tornado was approximately 1.3 km wide, did damage along a 19 km long path with at least some of that damage being EF2.

To make things even more confusing, satellite tornadoes orbited around the main circulation, an usual situation for Ontario. Dr Sills told me that the damage done by the central tornado was mostly due to suction vortices, small, violent swirls within the wall of the tornado, as opposed to one central path of destruction and thus, left a very complex damage pattern.

The supercell continued on an almost due east direction, producing yet another tornado in Harriston, this time an EF-1, 500 metres wide, and with a damage path 9.5 km long.

Racing southeast along the highway towards the town of Lucknow, I knew that I needed to get south of the tornado to both be safe and to see the tornado itself. What I didn’t know was that the massive green wall of rain, hail and cloud to my east was the tornado itself, but I finally figured it out moments before I led everyone around me into the tornadic circulation itself.

I slammed on the brakes and dove the car into a farm lane, skidding to halt as the wall of rain swept past and then, moments later, the core of the storm exploded over us. Hail, rain and wind slammed into the car, but I knew that we were now safe from the far more terrible winds to our south. Given that the tornado itself was nearly invisible in the rain and wind, it was better to stop and get run over by the core than drive into a non-visible tornado.

Thanks to the extra moisture added to the atmosphere by the Great Lakes, tornadoes in southern Ontario are often hidden in the rain that wraps around the central, spinning mesocyclone. This gives them an added level of danger as you often can’t seem them until they’re on top of you.

As the hail and rain in the core slowed to a trickle, I headed south to see if there’d been damage done to the town. Very quickly I found areas of damage which didn’t conform to the usual damage I’d expected from a tornado the size I’d seen. I called Dr. Sills, letting him know that I was pretty sure that something big had just rolled through the town. The Northern Tornadoes Project rolled into gear to figure it all out, but it was about to prove to be one of the more complex studies that they’ve done.

We got lucky. Despite the size and complexity of the tornado, it inflicted no casualties and no injuries. Its only legacy was an unusual damage path and mereological conundrum of what exactly happened in the heart of the supercell.