How a volcano half a world away once stole Canada's summer

The volcano's 1816 eruption triggered a temporary climate change that had catastrophic consequences.

Canada's reputation as a winter nation overlooks its summers, which are often marked by extreme heat and clinging humidity, depending on where you are.

Not everyone is a fan. But if you struggle with the extreme heat, it might be useful to look back to the year much of Canada pretty much lost out on the season.

We're talking about the summer of 1816, where frost was recorded every month of the year, a two-foot snowfall showed up in June, and a prolonged cold spring wreaked havoc on farmers' planting schedules, contributing to food shortages that had been years in the making.

That miserable year wasn't a random glitch in Earth's climate. It was a direct effect of one of the most destructive volcanic eruptions in all of history: Indonesia's Mount Tambora, which blew its top in April 1815.

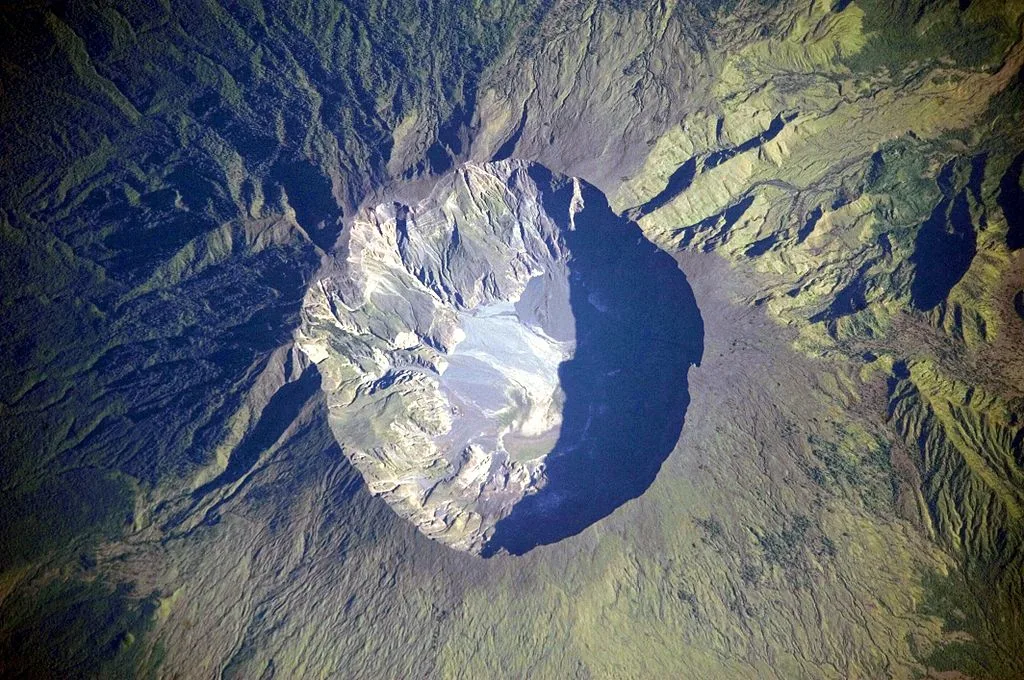

The most powerful recorded volcanic eruption took place in 1815 at at this active stratovolcano. (Google Maps)

DON'T MISS: Tonga volcanic eruption released more energy than most powerful nuclear bomb

The blast was powerful enough that some 70,000 people in the area are believed to have died as a direct result. Wired says hundreds of thousands of other deaths worldwide, due to famine and disease, can be attributed to the catastrophic changes in Earth's climate and weather that occurred as a result of the explosion.

So how did that one volcano wreak enough havoc with the climate to rob Canada of its summer more than a year later?

Aside from the sheer force of the blast -- the volcano was notably shorter afterward -- it also spewed millions upon millions of tons of volcanic ash into the atmosphere, along with volcanic aerosols.

That sort of material tends to linger in the atmosphere, and Tambora coughed out just so much of it that it reduced the amount of sunlight Earth received. Global average temperatures actually fell by a little more than half a degree.

That doesn't sound like a lot, but our climate exists in such a delicate balance, it was enough to cause major changes in the world's weather the following year.

This detailed astronaut photograph depicts the summit caldera of the volcano. (Source: Wikipedia/NASA Earth Observatory)

DON'T MISS: The place in Canada where the cliffs are always smoking

In eastern North America, the consequences were particularly dire. Though Canada didn't get the worst of it, the temperature roller coaster that ensued came on the heels of several years of bad harvests (according to Canada's History Magazine), adding to the various colonies' already precarious food security.

Snow lingered on the ground well into May in many places in eastern Canada, meaning a late start to planting. And although, as sources at the time say, proper rains and more seasonal temperatures did return, early June saw one of Canada's most legendary snowfalls.

Macleans says by the time the flakes had stopped falling, snow blanketed the burgeoning colonies' major cities of Kingston, Montreal and Quebec City. The latter was particularly hard-hit, with the sources speaking of snowdrifts two feet deep, and reports of ice "as thick as a dollar" coating plants.

The cold snap killed livestock and caused major distress in Canada (though some sources note the northeastern United States was hit even harder and more consistently). Looking ahead, the late start to the spring had delayed the growing season, and although reports from the time seem to suggest later crops were actually doing OK until a bad frost in September and early snow in October devastated them before harvest, particularly in Lower Canada (today's Quebec) and New Brunswick.

Lower Canada responded to the resulting scarcity by restricting food exports, as did the Maritime colonies. In Newfoundland, a boatload of would-be immigrants was turned away due to lack of food in St. John's, according to Canada's History. In Upper Canada, the future Ontario, the crops did better, and export restrictions weren't imposed, so the colony could send food to its neighbours -- but Upper Canada would take a bad hit the following year, thanks to bouts of frost and crop disease in late 1817.

Colonial governments spent the modern equivalent of millions of dollars in relief to help the worst-affected. Maclean's says grain was also imported from Russia and the United States -- the latter of which saw excellent crops in the then-sparsely populated Midwest, prompting a major wave of pioneers from the eastern states to up stakes and head west.

That's what Canadians' ancestors were coping with, a little more than 200 years ago. Aside from providing a certain perspective, the sobering takeaway is that this massive hardship came about due to a change in global average temperatures of less than a degree.

So when climate scientists sound the alarm about the world getting one, two or three degrees hotter in the coming decades, the Year Without A Summer should give you an idea why they're so worked up about it.

SOURCES: Wired | Canada's History | Maclean's | Canada's History