Over 150 years of forecasting in Canada, here's what's changed – and what hasn't

The technology and scale may have evolved, but Canadians' uncommon preoccupation with the weather hasn't abated one bit.

Everybody has an opinion about the weather, so the saying goes. You might call it the one thing everyone has in common.

Forecasters back up those opinions with science and probability, to give you as good a sense as they can how the weather will turn out. And they’ve had plenty of time to fine-tune the process. This year marks 151 years of the Meteorological Service of Canada – one of the first of its kind in the world, and established only a decade after weather forecasts began to be published in the U.K.

A lot has changed in that time, but David Phillips, senior climatologist at Environment and Climate Change Canada, says one thing that hasn’t much changed is Canadians’ unique relationship with their weather.

“It doesn’t matter where you travel in Canada, there’s a need to know what the weather is going to be that day,” Phillips said in an interview with The Weather Network. “Could be for a 25-cent decision, could be for a multi-million dollar life-saving kind of issue; whether you’re going out on a lobster boat or pouring cement, there’s that need to know how that atmosphere is going to unfold.”

When the first Canadian weather service was established by Parliament in Toronto on May 1st, 1871, with a princely $5,000 in funding, Canada, just shy of its fourth birthday, was a very different country.

The new dominion consisted of only five provinces, home to fewer than 4 million people. The soon-to-be sixth province, British Columbia, with its famously balmy coasts and snowy mountains, was weeks away from joining Confederation.

Meteorological employees launching one of the first upper air weather balloons at Varsity Stadium in Toronto, next to the weather headquarters at 315 Bloor Street, circa 1929. Credit: City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 8141.

Most of the country’s territory was made up of the Northwest Territories — back then sprawling to cover the entire Canadian prairie as well as the far north. By the time that new office in Toronto officially began recording weather data, the distant territories had been part of the country for less than a year, even though its Indigenous people had called the region home since time immemorial, far longer than the European traders who’d dotted the expanse with isolated trading posts.

And then, as now, Canada’s weather was very diverse, posing a challenge to meteorologists, who had to observe and forecast for landscapes ranging from high mountains and arid plains, through to dense woodlands, interconnected lakes, huge rivers, and jagged ocean coastlines.

Not only diverse, but prone to extremes as well, something Canada’s nascent meteorological service would have to learn to work with. Canada is the second most tornado-prone nation in the world. Its Atlantic coast sees the occasional hurricane. Temperature-wise, there might be a 70-degree difference between the coldest winter lows, and the highest summer peaks, depending on location.

In fact, Phillips says, one of the big triggers for Canada actually establishing its own meteorology service was to monitor storm risks on the Great Lakes, legendary for their numerous shipwrecks and low life expectancies of those who sailed on them.

WATCH BELOW: WHAT FUELS OUR METEOROLOGISTS

Those extremes may have helped fuel Canadians’ interest in a forecast that could very well spare them from a dangerous storm.

“Canadians are respectful of the weather,” Phillips says. “What amazes me is that...there are so few people that die from weather in Canada. More Canadians die from falling out of bed than die from the weather. And it’s because we have a good weather information forecasting service.”

When it came to those forecasts, aside from thermometers, barometers, rain gauges and other such simple instruments, forecasters in 1871 had few of the modern assets we’ve come to take for granted. No radars to track severe thunderstorms, no satellites to keep an eye on Atlantic hurricanes, no computer models to help hammer out seasonal outlooks like The Weather Network’s spring forecast.

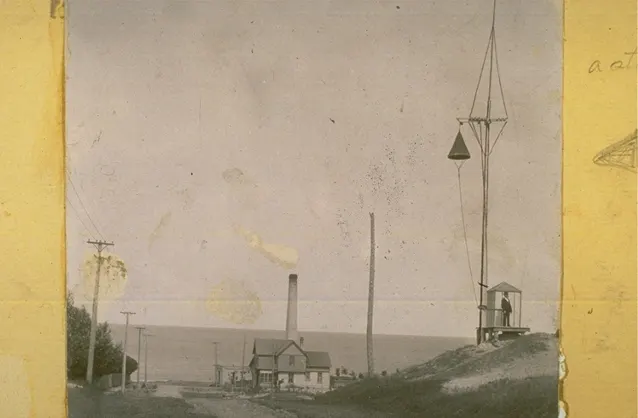

System of cones and barrels at a marine port on the Great Lakes, circa 1920s. The system was used for weather warnings on the Great Lakes and Atlantic Coast until the 1950s. Credit: City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 8141.

Communicating the forecast was low-tech as well. In some communities, people would walk to the train station or post office to check the weather. When newspapers began publishing the forecast, skeptical editors were baffled at how loudly their readers clamoured for them.

From these small beginnings, much has been accomplished, and the Meteorological Service of Canada continued to do its work after 1971, when it was folded into what is now known as Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), along with other organs such as the Canadian Wildlife Service and the Water Survey of Canada. In the 50 years since, ECCC has continued to safeguard the environment, leading the way on ozone depletion and acid rain in the 1980s, pioneering the world’s nationwide UV index in the 1990s, and grappling with the challenges of climate change in the 21st Century.

No longer just an office somewhere in Toronto, ECCC boasts 111 locations across Canada, with some 7,000 dedicated staff. But though the scale and tools have changed, the core goal of the weather service has remained the same: Observe, forecast, and communicate the weather to Canadians, who have more information than ever.

“I think there’s no excuse, doesn’t matter how, or where you are in Canada, you have access to a weather forecast, and I think that’s a remarkable achievement, in both the private sector and the public service,” Phillips says.

Editor's note: This article was originally published in March 2021.