One of the strongest ocean currents is speeding up, concerning scientists

Although the Southern Ocean is a remote part of the planet, scientists say that the warming occurring in this region could have impacts on the global climate.

Decades of data have revealed the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), the only ocean current that encircles the entire globe, has started flowing faster.

The ACC wraps around Antarctica and is a barrier between the tepid subtropical waters north of it and the cool waters to the south, helping keep temperatures low near the frozen continent.

The subtropical waters above the ACC have absorbed significant amounts of heat over the past few decades. In fact, over 90 per cent of the excess heat in the atmosphere created by greenhouse gases has been absorbed and stored in oceans since the 1970s.

The Southern Ocean, which is where part of the ACC flows through, has absorbed particularly high amounts of this extra atmospheric heat. Scientists have noticed that the additional heat is increasing the temperature difference between the two areas of water the current separates, which is causing it to flow at a faster rate.

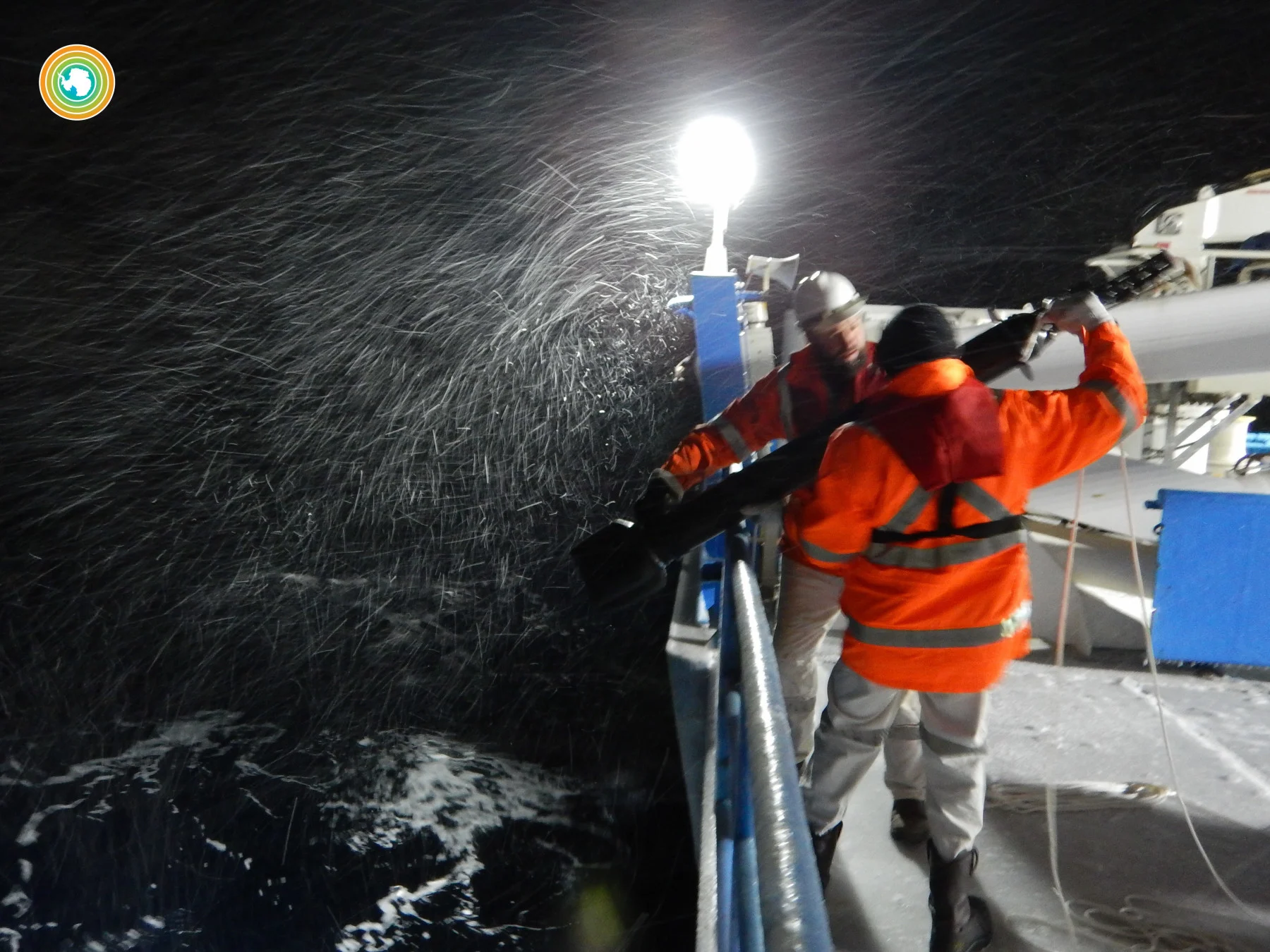

During a SOCCOM expedition on the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer, a scientist watches as a large wave enters the Baltic Room, where the operations crew deploys and recovers equipment. She is strapped into a safety line and is waiting for a moment to safely perform the task at hand. (SOCCOM Project/ Greta Shum)

The study, published in Nature Climate Change, used data satellites and Argo, which is a network of floating robotic instruments that record ocean conditions like temperature and salinity. There are currently 4,000 floats scattered across the world’s oceans that are collecting data.

Warming global temperatures have also been affecting prevailing westerly winds and causing them to energize ocean eddies, which are smaller, circular currents of water, near the ACC. However, these winds are playing less of a role in the ACC’s flow rate than the scientists initially suspected.

Scientists recording oceanic data near Antarctica. (SOCCOM Project/ Melissa Miller)

“The ACC is mostly driven by wind, but we show that changes in its speed are surprisingly mostly due to changes in the heat gradient,” said co-author Lynne Talley, a physical oceanographer at Scripps Oceanography, in the study’s press release.

“From both observations and models, we find that the ocean heat change is causing the significant ocean current acceleration detected during recent decades,” said Jia-Rui Shi, study contributor and postdoctoral researcher at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Between 2003-2019 Antarctica’s ice sheet lost an average of 118 gigatons of ice each year, making this continent one of the fastest-changing landscapes on Earth. Warming ocean temperatures exacerbate the melting that ice sheets are experiencing because they thaw the base of glaciers and enhance their breakage.

Global impacts are also possible if this region continues to warm abnormally fast since all the ocean currents act as a conveyor belt that circulates heat, nutrients, and carbon around the planet.

Thumbnail credit: SOCCOM Project/ Hannah Zanowski