World's oceans broke heat records again in 2021

Last year was at least the third year in a row for record-breaking ocean heat.

The world's oceans absorb a substantial amount of heat produced by global warming, and in 2021, a new record was set for heat content in the upper portion of the ocean's waters.

As Earth's climate continues to warm due to greenhouse gas emissions, only a small fraction of that heat becomes trapped in the atmosphere. In fact, since 1955, more than 90 per cent of the excess heat produced by global warming has been absorbed by the world's oceans.

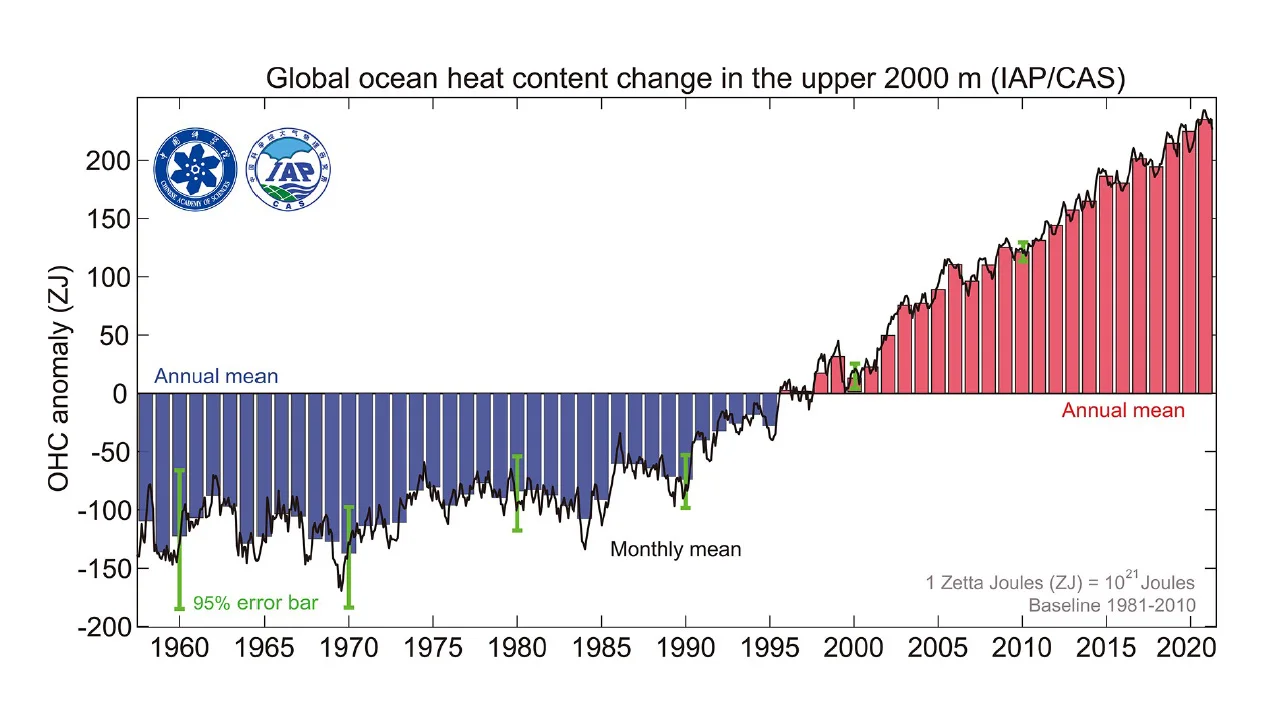

Scientists have been tracking ocean heat content for decades. Their measurements from the top 2,000 metres of our oceans show a far more steady rise in temperatures than we see with global surface and air temperatures. While surface temperatures ranked only sixth highest on record for last year, heat content in the world's oceans set a new record high in 2021.

This graph plots the heat content of the upper 2 km of the world's oceans, from 1958-2021, as measured in Zetta Joules (1 ZJ = 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 Joules, or 1 billion trillion Joules). While the black line represents monthly values, the bars are annual averages compared to the 1981-2010 average. As the graph reveals, at least since the mid-1980s, ocean heat content has been steadily rising. The last seven years, 2015 to 2021, are the warmest seven years, with 2021 now the hottest year for ocean heat on record. Credit: Cheng, et al., 2022

"The oceans are the most accurate 'thermometer' for the climate system," Michael Mann, the director of Earth System Science Center at Penn State University, told The Weather Network. "It's where we first go to measure the warming from human carbon emissions, and it shows a very steady rise over time, with 2021 the warmest now on record."

Mann is one of 23 international experts who contributed to a new study detailing the latest observations of heat content stored in the top 2,000 metres of the world's oceans.

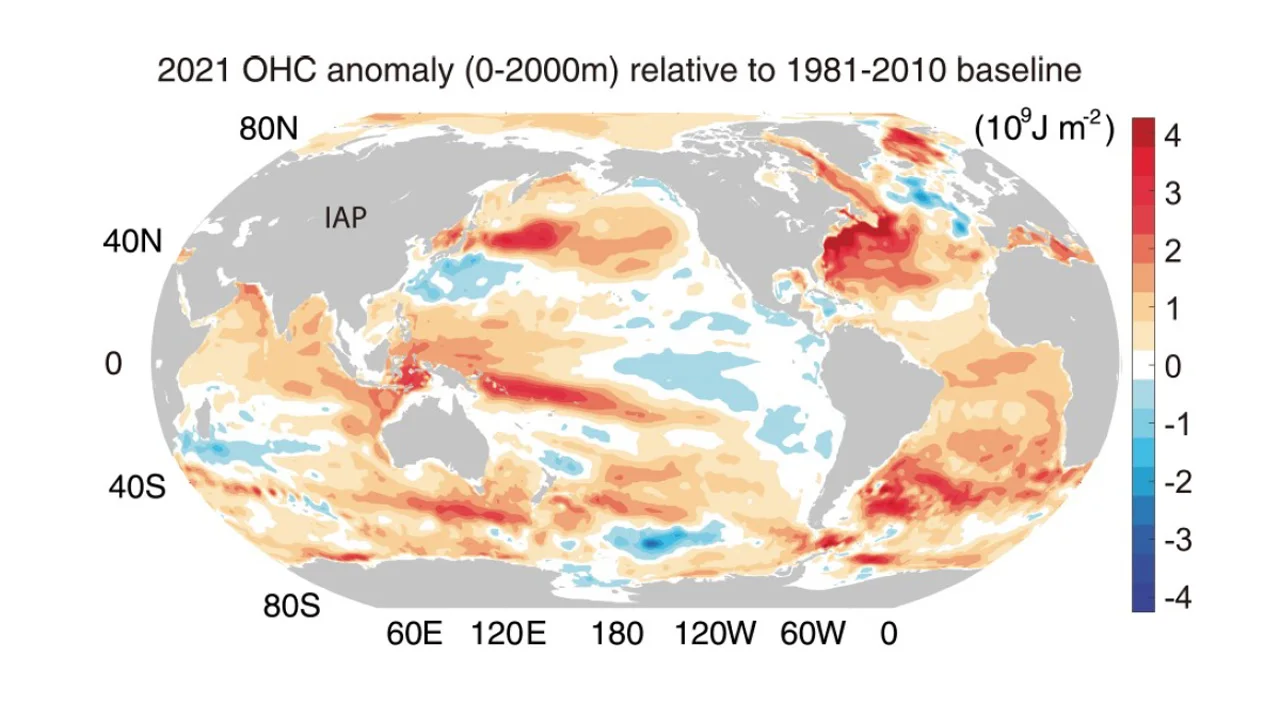

As NOAA wrote in their latest annual global climate report, based upon this study: "The annual global ocean heat content (OHC) for 2021 for the upper 2000 meters was record high in 2021, exceeding the previous record set in 2020. The seven highest OHC have all occurred in the last seven years (2015-2021). During 2021, the heating was distributed throughout the world's oceans, with record-high heat across the North Atlantic Ocean, the North Pacific Ocean, and Mediterranean Sea."

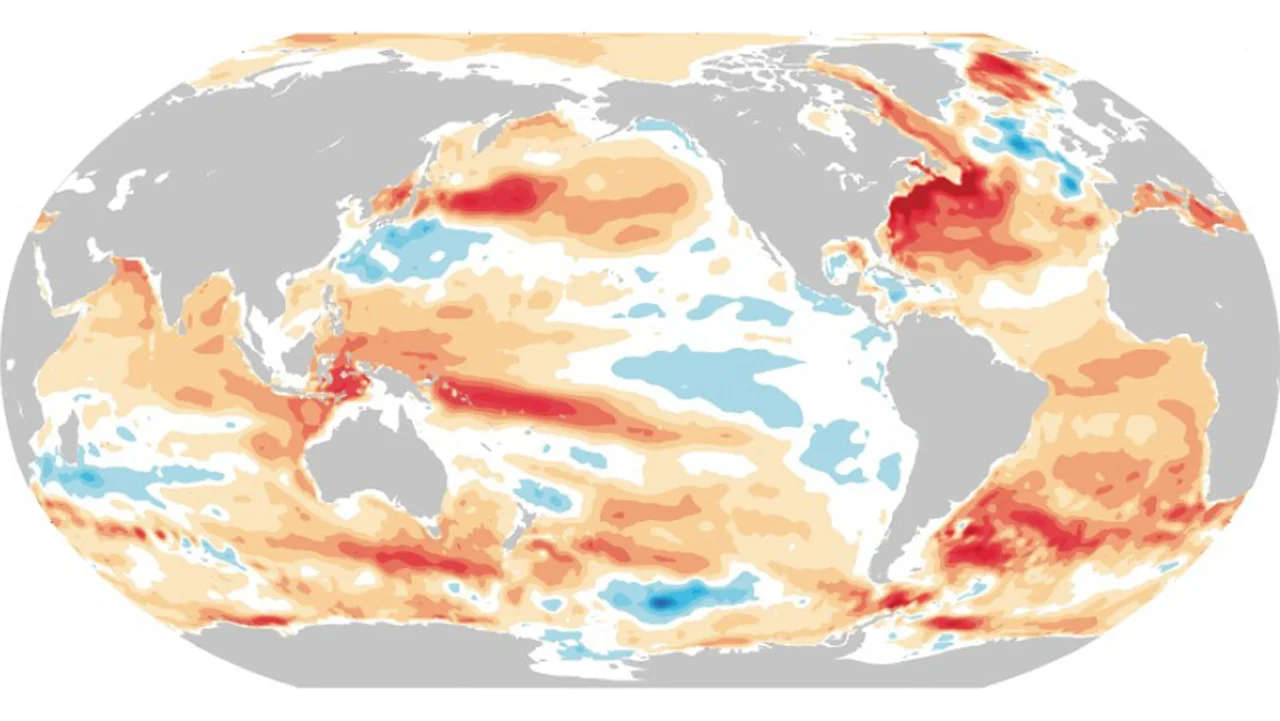

A map of ocean heat shows the relative hot-spots around the world in 2021, with largest anomalies in the North Atlantic, especially along the east coasts of the United States and Canada. The effects of La Niña can be seen in the relatively cool region to the west of northern South America. Credit: Cheng, et al., 2022

This new record was set despite the 'cooling' effects of last year's two La Niña patterns in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. While El Niño years tend to be warmer and La Niña years tend to be cooler, that is only on the ocean surface. The opposite effect happens in the waters deeper down.

As Mann explained, the extra warmth we see in surface observations during an El Niño year is due to heat escaping from the ocean to the atmosphere. Thus, the ocean subsurface layer cools slightly. Conversely, the cooling effect on the surface during a La Niña year actually traps more heat in the subsurface ocean, which is what helped boost this year's record ocean warmth.

"Stronger hurricanes, the demise of coral reefs around the world, including the now gravely-threatened Great Barrier Reef, declining fish populations, destabilization of ice shelves in the southern ocean with the threat of substantial disintegration of large parts of the western Antarctic ice sheet and not feet, but meters, of sea level rise. These are among the impacts we're seeing now, or will see soon, if we continue with business as usual burning of fossil fuels," stated Mann.

"The oceans will continue to warm until we bring net carbon emissions to zero," Mann added. "In short, we've got to transition off fossil fuels as quickly as possible."