How this deadly fungus rode a tsunami to British Columbia

The 1964 Great Alaskan Earthquake and its resulting tsunamis may be adding to their death toll, 55 years after the fact.

Since 1999, at least 300 cases of a mysterious fungal infection have been reported in British Columbia and parts of the U.S. Pacific Northwest. Roughly 10 per cent of those cases have proved fatal. But, before the first case was reported on Vancouver Island, the fungus responsible, Cryptococcus gattii, had only been observed in Papua New Guinea, Australia, and South America.

So how did this tropical fungus come to be in the soil and trees of Vancouver Island?

A newly-published study suggests that this sometimes-deadly fungus took an unusual route to shores of North America: it hitched a ride on the tsunamis spawned by the Alaskan quake -- the largest ever recorded in the Northern Hemisphere.

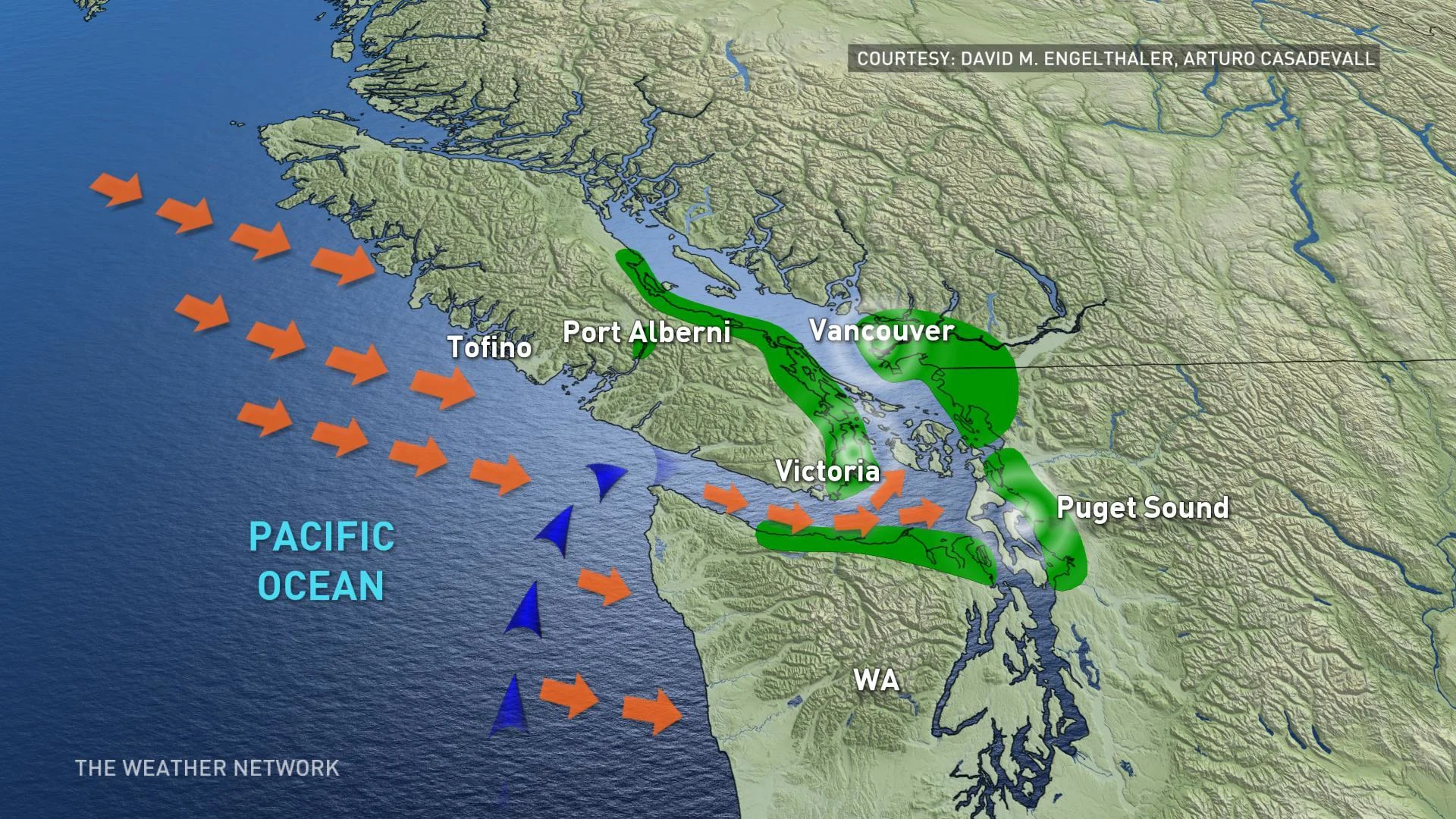

Researchers theorize the fungus first travelled to the region in the ballast tanks of ships travelling north from the Panama Canal but remained mostly offshore in coastal waters. It was the tsunamis sparked by the 9.2 earthquake that then washed the fungus ashore en masse.

*Calculated travel time map for the tectonic tsunami produced by the 1964 Prince William Sound earthquake in Alaska. Image: By NGDC - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0 *

"The big new idea here is that tsunamis may be a significant mechanism by which pathogens spread from oceans and estuarial rivers onto land and then eventually to wildlife and humans," says microbiologist Arturo Casadevall, one of the study's co-authors.

Fungal transport. Blue arrows represent shipping travel, orange arrows indicate water flow from tsunami waves. Green areas show where c. gattii is widespread in soil and trees. Based on an image from David M. Engelthaler, Arturo Casadevall.

The 30-year delay between the fungus' arrival onshore and the first infections noticed in humans and animals in the region is likely due to its time spent as a seafarer.

"We propose that C. gattii may have lost much of its human-infecting capacity when it was living in seawater, but then when it got to land, amoebas and other soil organisms worked on it for three decades or so until new C. gattii variants arose that were more pathogenic to animals and people," Casadevall says.

This discovery carries significant implications for the spread of disease following both more recent and future natural disasters. "If this hypothesis is correct," says Casadevall, "then we may eventually see similar outbreaks of C. gattii, or similar fungi, in areas inundated by the 2004 Indonesian tsunami and 2011 Japanese tsunami."

Sources: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health | EurekAlert | mbio.org |