Wildfire smoke increases risk of heart issues within hours, study finds

The B.C. Centre for Disease Control is again warning British Columbians of the negative health impacts of wildfire smoke, in the wake of new research that suggests air pollution can immediately increase risk of several heart problems.

For every 10 micrograms more of PM2.5 — the primary particle in B.C.'s wildfire smoke — in one metre cube of air, a person's combined odds of experiencing at least one of four heart issues was 5.5 per cent greater, a study published Monday in the Canadian Medical Association Journal found.

The four arrhythmia studied are all significant risk factors for heart attacks and heart disease, the study notes, supporting decades of evidence that shows higher rates of cancer, chronic disease and premature death in communities that live with poor air quality.

The findings highlight the urgency of limiting even short-term exposures to wildfire smoke amid smoke-related rises in heart attacks and respiratory issues researchers and health care workers are already observing in B.C., says one BCCDC expert.

"When there is wildfire smoke in the province, we do see increases in those types of negative outcomes within hours of the smoke arriving," said Sarah Henderson, scientific director of environmental health services at the BCCDC.

DON’T MISS: Big, small, or mini, here are our top picks for air purifiers this summer

WATCH: The 2019 B.C. wildfires caused an increase in mental health cases, psychologist claimed

DON'T MISS: Residents west of Edmonton under evacuation order due to out-of-control wildfire

Heart attacks, breathing problems, and weakened heart walls increased by about 1 to 2 per cent within an hour of exposure to more PM2.5, according to a 2020 study Henderson co-authored.

"It's a small but important number," Henderson noted.

Dr. Lori Adamson, an emergency physician in Salmon Arm, B.C. — about 111 kilometres north of Kelowna — says she sees first-hand the influx of patients struggling to breathe who come to hospital on smoky days, and that in turn puts pressure on their hearts.

"My patients are very distressed about the situation and they come in kind of feeling desperate and hopeless … because it feels like a really big problem and outside of their control," said Adamson.

Adamson adds the majority of — as well as the most vulnerable — people she admits to hospital are infants and children, whose lungs are more delicate and who breathe faster than adults, and people with pre-existing respiratory conditions like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that are exacerbated by the smoke.

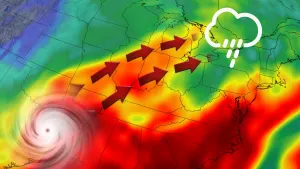

WATCH: Thunderstorm risk increases wildfire concerns for B.C. and Alberta

SEE ALSO: What’s in wildfire smoke? Toxicologist explains health risks, best masks to use

'Action at a broader scale' needed

The peer-reviewed study is based on data from nearly 200,000 patients in 322 cities in China between 2015 and 2021, where coal-burning means air pollution is more persistent and of different chemical proportions than in B.C.

The findings are concerning for B.C. because the size of the particle matters more than the composition, Henderson said. PM2.5 is smaller and can penetrate further than other molecules, blocking even more oxygen exchange.

"We don't know much about this right now but if you protect yourself from these exposures in the short-term, you're also protecting yourself in the long-term," said Henderson.

Children play on Hot Sands Beach in downtown Kelowna, B.C., amid heavy wildfire smoke in July 2021. New research published Monday suggests air pollution can immediately increase risk of several heart problems. (Winston Szeto/CBC)

Henderson suggests using air purifiers with HEPA filters to clean air at home, wearing well-fitted N95 and KN95 respirators if spending time outside, and to avoid exercise and heavy breathing on smoky days.

Anyone struggling to breathe, particularly young children and older adults, should seek medical care. "We do have to look at these individual level interventions and behaviours to help reduce exposure and impacts within the population," said Henderson.

For Adamson, a member of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, more needs to be done by government at all levels to prepare people for the health impacts of wildfires and move away from fossil fuel-based energies that drive climate change and worsen wildfires.

"There needs to be action at a broader scale … so we're not just figuring out how to deal with smoke in our faces."

This article, written by Moira Wyton, was originally published for CBC News.