Invasive Asian 'murder' hornets pose serious threat to honeybee populations

The two-inch Asian giant hornets are known to violently attack their prey, especially honeybees

These insects may sound like they're from a horror movie, but they're all too real, especially for the honeybees that they particularly like to prey on.

Asian giant hornets have made their way into North America, specifically in Washington state in the U.S. and here at home in British Columbia. Beekeepers in the states have reported scores of dead bees with their heads torn off, which isn't good news for the already rapidly declining honeybee population.

SEE ALSO: Canadian scientists closer to solving honeybee die-off mystery

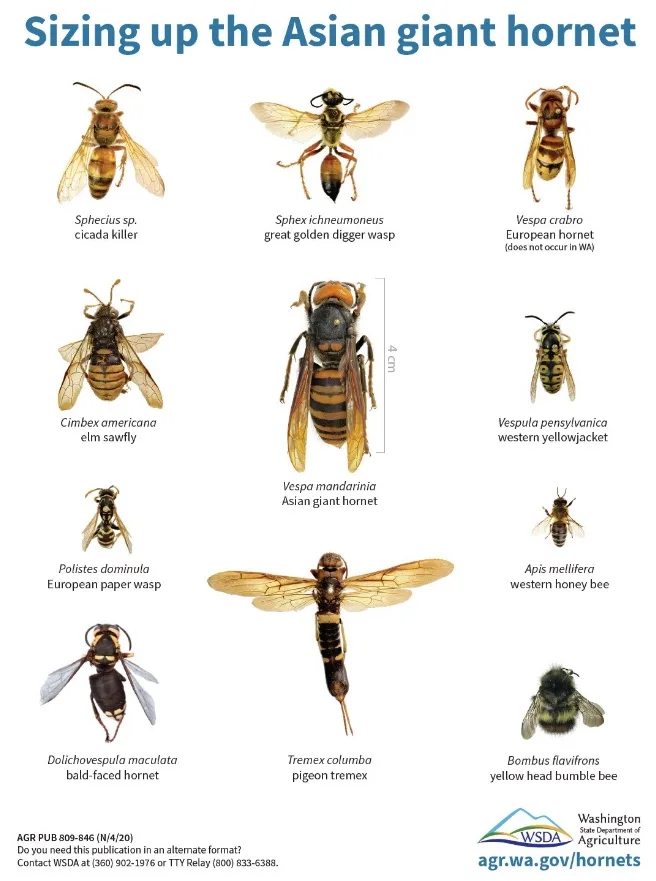

Their size and appearance are fairly distinct, compared to wild hornets. At more than two inches long, they're considered to be the world's largest hornets with a sting that can be deadly to humans if they are bitten numerous times, say experts at Washington State University.

Because of their violent tendencies, researchers haved dubbed them "murder hornets."

"They're like something out of a monster cartoon with this huge yellow-orange face," Susan Cobey, a bee breeder at the Washington State University (WSU)'s department of entomology, said publicly recently.

HOW THEY CAME TO NORTH AMERICA

There is still discussion surrounding the circumstances of how the invasive insects native to Asia found their way to the United States and Canada. Current speculation is they're sometimes transported in international cargo, in some cases deliberately, according to Seth Truscott of WSU's college of agricultural, human and natural resource sciences.

The giant hornet was first discovered in the state in December. Scientists believe it became active again in April, when queens move out from hibernation to build nests and form colonies.

Comparison of the different types of hornets. Photo: Washington State Department of Agriculture.

"Hornets are most destructive in the late summer and early fall, when they are on the hunt for sources of protein to raise next year's queens," Truscott said in WSU's Insider.

"They attack honeybee hives, killing adult bees and devouring bee larvae and pupae, while aggressively defending the occupied colony," he added. "Their stings are big and painful, with a potent neurotoxin. Multiple stings can kill humans, even if they are not allergic."

State officials have asked beekeepers and residents to report sightings of the giant hornets, but to avoid getting too close. The sting can pierce the average beekeeper's suit and state scientists have to wear special reinforced outfits.

HONEYBEES UNDER THREAT IN SUMMER, FALL

The giant hornets will typically target honeybees between late summer and the fall.

"Traps can be hung as early as April if attempting to trap queens, but since there are significantly fewer queens than workers, catching a queen isn't very likely," the Washington State Department of Agriculture said in a statement.

Asian giant hornet. Photo: Washington Invasive Species Council

Traps are in place and an app was launched to report timely sightings, as just a few of the hornets can destroy a hive within hours.

SIGHTINGS IN LOWER MAINLAND, B.C.

In March, The B.C. Ministry of Agriculture asked Lower Mainland residents near the Canada-U.S. border to look out for the Asian giant hornet.

The insect, about twice as large as native B.C. hornets, was discovered for the first time in the province in August 2019 in Nanaimo. The nest was located and destroyed. Officials believe they came from an ocean vessel.

A press release issued from the agency in March stated a single giant hornet then turned up in White Rock last November, while a pair of them were found just across the border, near Blaine, Wash., in December.

Because wooded areas near the border are considered to be an attractive habitat for the hornets, authorities believe there may be an overwintering queen in the vicinity that will emerge with the warmer weather to start a new nest.

Thumbnail courtesy of Washington Invasive Species Council.

Sources: CNN | The Georgia Strait