Police raid turns up rare flying reptile fossil

The discovery will provide new insight into the reptile's behaviour and ecology.

A 2013 police raid turned up the most complete pterosaur fossil found to date, according to a recently published paper appearing in the journal PLOS ONE.

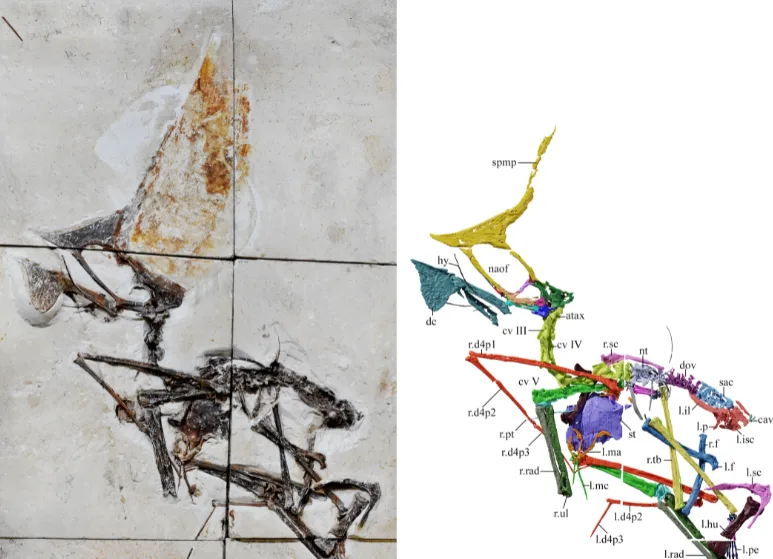

Almost the entire body is preserved, as well as some small tissue. That's a far cry from previous specimens, which usually just consisted of the skull. The fossil belongs to a species known as Tupandactylus nagivans and it lived during the Early Cretaceous period, between 100.5 and 145 million years ago.

It was found during a police raid at São Paulo's Santos Harbour and seized along with 3,000 other protected relics.

"The Federal Police of Brazil was investigating a fossil trade operation and recovered, in 2013, over 3,000 specimens," study author Victor Beccari, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of São Paulo, said.

"Fossils in Brazil are protected by law, as they are part of the geological heritage of the country. Therefore, collecting fossils requires permission, and the trade and private collections of fossils are illegal in Brazil."

Sketch of T. Navigans, stylized and animated by Cheryl Santa Maria. (Dimitry Bogdanov/Wikipedia CC BY SA 3.0

Once collected, the slabs were transported to the University of São Paulo and re-assembled like puzzle pieces, using a CT scan to locate bones. Beccari's team started studying the fossil in 2016.

The pterosaur in the fossil had a wingspan over 2.5 metres and was 1 metre tall, with 40 per cent of its height consisting of its head crest. Because it also had a long neck, which also had a crest, researchers suspect it was a short-distance flyer.

A photo of the specimen. (Baccari et al/PLOS ONE)

"The skeleton shows all the adaptations for a powered flight, which the animal may have used to quickly flee predators," Beccari said.

Researchers said the findings will help paint a better picture of how the reptile moved and behaved.

"This specimen allows us to understand more about the complete anatomy of this animal and brings insights into its ecology," Beccari said.