Invasive species you may not know that threaten Canada’s biodiversity

Invasive species rank as the second-biggest threat to wildlife and biodiversity in Canada and around the world, according to the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC).

Remember when Asian giant hornets caused undue public hysteria in 2020? While they aren’t viewed as a threat to humans, they can cause significant ecological harm as an invasive species in this country — one of thousands in Canada.

Invasive species are a significant problem, ranking as the second-biggest threat to wildlife and biodiversity in Canada and around the world, according to Dan Kraus, current director of national conservation with Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, and a former senior conservation biologist with Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC).

SEE ALSO: Asian giant hornets: A lot more buzz than sting, experts say

As part of the recent Invasive Species Awareness Week (ISAW), the annual campaign in Canada draws attention to species such as the Asian giant hornet and the LDD (Lymantria dispar dispar) moth caterpillar and the threats they pose to our ecosystems.

Kraus spoke to The Weather Network in 2020 (with NCC at the time) on some of the most threatening invasive species in Canada. He said early detection and eradication is critical in the fight to prevent the spread of or remove invasive species.

“Identifying those Asian hornets and trying to remove them quickly, that’s exactly what we want to do for invasive species. That early detection and eradication. If we had done that with zebra mussels decades ago, the Great Lakes would be a healthier environment now. We would have saved ourselves billions of dollars in terms of the economic cost they have caused,” said Kraus.

Speaking of financial cost, just the invasive plants alone cost Canada’s economy approximately $2.2 billion each year, according to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). They do this by reducing crop yields and quality, and increase the costs of weed control and harvesting.

Woodland angelica. (Nature Conservancy of Canada).

“Most invasive species, once they’ve been established, they’re here to stay. It’s unlikely we will eliminate them. It’s more how can we manage them and keep them in check so they’re not affecting our native plants and animals,” said Kraus.

SPECIES VARIES BY LOCATION

While it’s hard to pinpoint the exact number of invasive species in Canada, it’s safe to say they number in the thousands. The ones that pose the most risk to our environment depends on where you live in the country, Kraus said.

For example, in Ontario, some of the worst species include the dog-strangling vine, originally from parts of Europe. It can grow very quickly, and as it does, it displaces many of the native vegetation, Kraus said.

“It’s not that our native species are weak or are non-competitive, it’s just that this thing shows up and none of our native predators know what to do with it, [allowing] it to take off," said Kraus.

Another potent invasive species in Ontario is European common reed or sometimes referred to as phragmites, which is also spreading to western provinces. Kraus describes it as a “tall, feathery, grass-looking plant” you will often see on the side of highways.

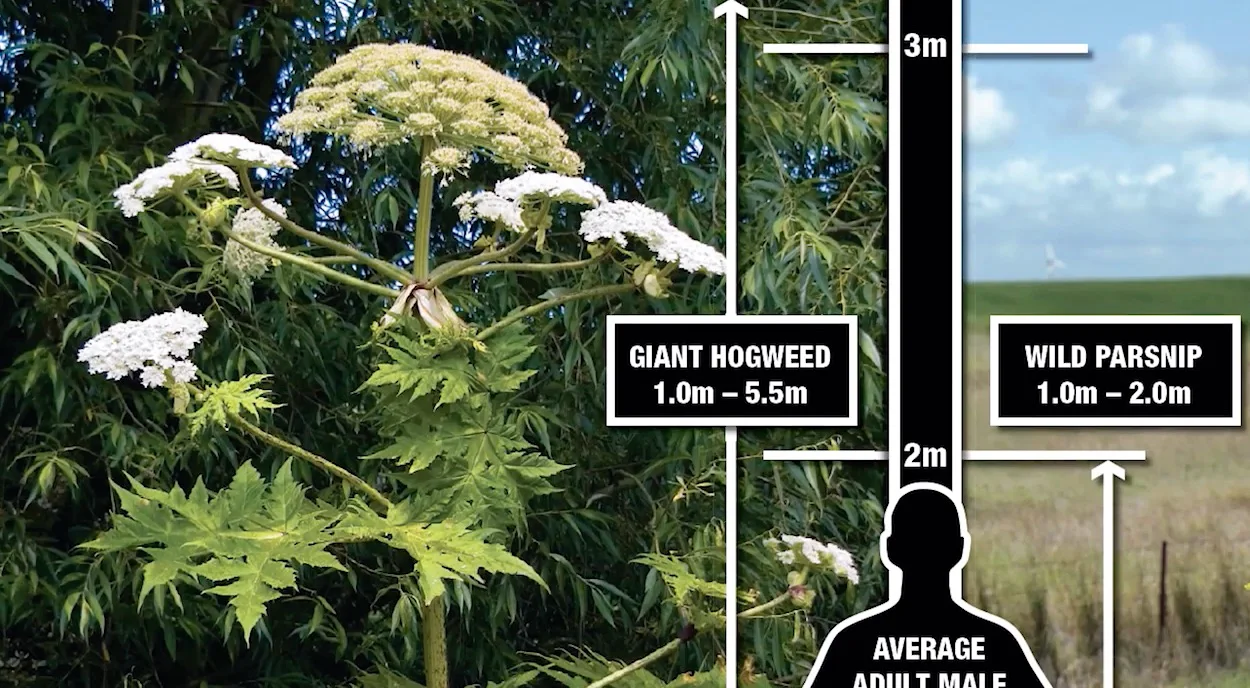

Giant hogweed, which can cause blistering, is a species that can be found in gardens, originally brought in as a horticultural plant. “People don’t grow it anymore, but it has moved out of gardens and has spread into natural areas,” said Kraus.

Giant hogweed. (Conservation Halton).

One way people can help identify an invasive species is to take a picture of it on their cellphone and upload it to iNaturalist using its associated app. Experts can identify the species and point them in the right direction to have it removed.

“It may be one of our best defences against keeping new invaders out and also tracking the spread and new locations of invasive species that are already established,” said Kraus.

People can also report sightings of invasive species to their provincial agency that deals with them. A list of organizations can be found here.

GREAT LAKES ARE ONE OF CANADA’S MOST HEAVILY IMPACTED ECOSYSTEMS

The Great Lakes region is home to nearly 200 invasive species, one of Canada’s most heavily affected ecosystems.

A lot of the aquatic invaders in southern Ontario arrived here in ballast water from ships in the Great Lakes region. When the water was dumped in the lakes, the waterways saw an influx of invasive species such as round gobies, zebra and quagga mussels and spiny water fleas, just to name a few. They can spread unknowingly when attaching themselves to bait buckets or on the bottom of your boat, for example, Kraus said.

“There are campaigns now to make sure that if you’re doing some kind of water activity, to make sure you’re cleaning and drying your equipment thoroughly before moving it into another body of water,” said Kraus.

Zebra Mussels. (YouTube screenshot).

Zebra mussels have spread beyond the Great Lakes and have established themselves in many inland waterways such as lakes Simcoe and Couchiching, and even outside of Ontario, in Lake Winnipeg, Man., among others. The main form of transportation for the zebra mussels is through recreational boating, possibly fishing, too, the biologist noted.

“There will be some native animals that will figure out what to do with [the invasive species] that are all over the place. Whitefish, lake sturgeon, a lot of diving ducks will eat them [zebra mussels], as well,” said Kraus.

COMMON INVASIVE SPECIES IN BACKYARDS OR LOCAL PARKS

Gardening is one of the ways that some invasive species spread, so spring is a good time to learn about what you are growing, which may be non-native. In addition to planting native species, people can eliminate the possibility of spreading invasive plants by not dumping garden waste over the fence into a nearby park or ravine.

Below is a list of common invasive species you may encounter while walking along a trail or in your own yard.

Emerald ash borer: This non-native invasive beetle has decimated tens of millions of ash trees and continues to spread rapidly. It can quickly kill large areas of ash trees, impacting forests, areas along streams and rivers and urban forests and woodlands. It has spread to new areas where people have moved firewood cut from infected ash trees. Where it’s found: Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick.

Leafy spurge: This plant has yellow-greenish flowers and its leaves and stems have a white, milky sap. It probably came to Canada in grain seeds from Europe. It spreads quickly in open areas and threatens habitats, such as tall-grass prairie in Manitoba. In Saskatchewan, beetles have been introduced to the area as a biological control. Where it's found: Yukon, B.C., Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, P.E.I.

Leafy splurge. (Nature Conservancy of Canada).

Japanese knotweed: It resembles bamboo and was likely introduced as a garden plant, but Japanese knotweed can form dense thickets and out-compete native vegetation. It's particularly a problem where it takes over the edges of creeks and lakes. It's been identified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as one of the world's worst invading species. Where it's found: B.C., Alberta, Ontario, Manitoba, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, P.E.I., Newfoundland and Labrador.

Japanese knotweed. (Nature Conservancy of Canada).

Garlic mustard: Native to Europe, this green-leafed herb with white flowers spreads through forests and displaces native wildflowers and tree seedlings. Each plant produces thousands of tiny, black seeds that are viable in soil for many years. The only bright spot: The leaves can be picked and turned into a tasty pesto. Where it's found: B.C., Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, P.E.I.

Buckthorn: There are two kinds of this shrub — glossy false buckthorn and common — which have berry-like fruits that produce large number of seeds. This plant spreads quickly and prevents native trees and shrubs from regenerating. Common buckthorn is also the primary host for the non-native soybean aphid, a serious threat to farmers. Where it's found: Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, P.E.I.

WATCH: THIS INVASIVE PLANT CAN CAUSE SEVERE PAIN AND IT'S SPREADING ACROSS CANADA

Common tansy: This plant with yellow, button-like flowers can grow as tall as 1.5 metres. It was introduced to North America from Europe in the 1600s as a horticultural and medicinal plant. It impacts stream banks and native grasslands, and out-competes native plants. It also produces a toxic compound that can impact cattle and wildlife. Where it's found: Everywhere except Nunavut.

European swallow-wort/dog-strangling vine: This vine can grow up to two metres long and create dense thickets or grow on other plants. Monarchs have been known to confuse the plants with their milkweed host plant and lay eggs on it, but the larvae can’t survive. The plant invades forests, stream banks, grasslands and alvar habitats (limestone plain). A moth from the Ukraine area has been approved for release in North America as a biological control. Where it's found: B.C., Ontario, Quebec.

Purple loosestrife. (Nature Conservancy of Canada).

Purple loosestrife: This plant is listed as a noxious weed in many provinces, but is still sometimes sold as an ornamental plant. Before adding it to your garden, you should know it crowds out most native vegetation and creates near-monocultures. It has been identified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as one of the world's worst invading species, as a single purple loosestrife plant can produce more than 2 million seeds each year. Where it's found: B.C., Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, P.E.I., Newfoundland and Labrador.

Thumbnail courtesy of Nature Conservancy of Canada.

Follow Nathan Howes on Twitter.