We know the human costs of wildfires, but what about our wildlife?

We're just beginning to understand a wildfire's impact on an ecosystem. Fires play complex roles that become even more perplexing when wildlife are in the mix. University of British Columbia (UBC) experts provide some insights

Visit The Weather Network's wildfire hub to keep up with the latest on the active start to wildfire season across Canada.

As Canada contends with what has been deemed its worst wildfire season this century, attention should also be turned to the ecosystems left in the wake of the blazes and what happens to the animals that dwell within.

Instinctively, people may want to focus on the damage and mortality rate of each event, but that’s not how researchers decipher the ecological impacts.

SEE ALSO: In the wake of wildfires, forests’ ability to trap carbon ‘goes up in smoke’

Karen Hodges, a professor of conservation ecology at the University of British Columbia (UBC), said the focal point should be on the "many decades of habitat change that follow after the fire."

"That's what will affect wildlife recovery, sustainable populations [and] the ecosystem coming back into some sort of resemblance of its former self," said Hodges, in a recent interview with The Weather Network. “Wildlife research right now is focused on once the fire is out, then what happens for days, weeks [and] decades after that.”

(Getty Images-1329940102)

Similar impacts of smoke and fire on wildlife, humans

While not studied extensively, there is documentation showing the similarity of physiological and physical impacts of smoke and fires on animals and humans, Hodges said.

“It's not great to be breathing really polluted air that damages lung function. There's also some evidence that it will alter bird migration routes," said Hodges, noting there was some suggestion a few years ago that birds were delaying or changing movements around sizable smoke plumes.

She said researchers don't have sufficient data on the specific elements of the fire that kills animals.

For example, if you have a nest of birds in a tree that burns, "we don't actually know if those animals were killed because they inhaled smoke before the fire [reached] the nest, or if it was the fire and heat that burned the animals to kill [them]," she said.

"We do know that animals do die in fires. There's been documentation of some really prominent fires, like the Yellowstone 1988 fires," said Hodges. "The rangers did identify some bears, elk [and] bison that had been killed in those fires."

(Getty Images - 1491031417)

Hodges "strongly" suspects that the stronger the fire is, the faster it burns -- increasing the likelihood of the death of an animal in the blaze as opposed to an individual that is on the fringe of it.

Surviving the wildfires and returning to the burned-scar regions

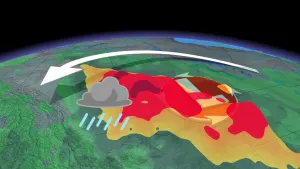

Lori Daniels, a UBC forestry professor and wildfire expert, said wildlife will either need to disperse to somewhere safe or find a way to survive through the fire.

"Animals like snakes, turtles and salamanders...many of those are going to go to underground burrows, if they can. The amazing thing is that the heat of the fire, in general, kind of stays near the surface," said Daniels, in a recent interview with The Weather Network.

However, if the fire burns for a long time, the heat will penetrate into the ground. But, if the animals can get into the mineral soils and burrows that are deep enough down, the temperatures will remain fairly cool and they should be able to survive, Daniels added.

(GettyImages-1057369516)

What can be barriers to wildlife escaping are livestock fences, for example.

"It's heartbreaking [when] there are fatalities and injured animals. When they can't escape from the fire, I, like many [others], will find it just really, really upsetting," said Daniels.

In the cases of some species, the sight of smoke is "quite likely" a signal for them to quickly flee the fire, Hodges said, but researchers don't know that with absolute certainty due to a lack of data and a difficulty in knowing beforehand where a wildfire is going to burn.

The good news is that many animals do have a chance of survival, no matter how big the fire gets, Hodges added.

“The bigger the fire, the more within fire heterogeneity there will be. There will be places where there's still a lot of green trees left," said Hodges. "We can have animals that didn't move away from the fire, but were able to survive where they were within the overall fire scar.”

WATCH: What role does climate change truly play in wildfires?

Some will quickly return to the burned-scar regions through their travels while others will begin to thrive in the areas the following spring, Hodges said.

“These are species that can capitalize on this rapid regrowth and the disturbance that just happened," said Hodges.

“If they're relying entirely on regeneration after a fire, then it's a matter of how quickly the trees regrow. We know that it depends on soil condition, moisture slope...things that affect tree growth.”

But it "entirely depends on the habitat pattern within that burn scar, and then the biology of each individual animal," Hodges added.

Mortality numbers aren't surveyed

Although researchers know a great deal about how animals respond to habitat changes from wildfires, the mortality rate of species from any given event isn't known since data is difficult to obtain and there are no post-fire surveys conducted, Hodges said.

"One of the big things we would need to know is how many animals were present prior to a fire burning," said Hodges.

(Warren Howes)

DON'T MISS: What role did climate change play in Alberta’s wildfires?

"To then be able to get a sense of how many animals escaped, died, stayed in place, but survived...that's really hard data to get, even just the post-fire piece. To get those data from a place you've surveyed prior is extraordinarily difficult."

Fires are vital for ecosystems

Wildfires, however, do serve a purpose in maintaining "resilient and healthy" forest ecosystems and sustaining habitat for a diversity of wildlife, especially over the long term, Daniels said.

"Because we've been so good at putting out fires in recent decades, we've lost the kinds of habitats that are critical for many wildlife. We're losing the diversity of habitats across landscapes as the forests become more homogeneous, as we, cumulatively, over time, put out many, many wildfires," said Daniels.

(Getty Images-493251462)

As well, a prescribed or controlled blaze -- a knowledgeable and contained application of fire to a specific area to accomplish planned resource management objectives -- is one of the most ecologically appropriate and relatively efficient way for obtaining planned public safety and resource management objectives. For example, it could be to enhance a habitat, prepare an area for tree planting or for disease eradication.

Prescribed fires are typically executed in various ways. They involve mitigating fuels, ecological restoration or a cultural application of fire by Indigenous communities, Daniels said in a 2022 interview with The Weather Network, noting they often happen in the spring or the fall under cool, wet conditions.

"They're going to be typically lower-severity fires. That means that they're emitting a lot less smoke than these high-severity fires that are burning under extremely hot, dry conditions, and generating a lot of smoke into the atmosphere," said Daniels, in the May 2023 interview.

One of the projects Daniels is involved with is a collaboration with fellow UBC instructor, Suzie Lavallee, alongside the Canadian Wildlife Service to conduct "forest thinning" and prescribed burning in the Vaseux-Bighorn National Wildlife Area in B.C., she said.

(Getty Images)

"We're working with the Canadian Wildlife Service to go into those dense patches of trees and figure out what is the best way to remove some of those understory trees that have grown in the absence of fire," said Daniels. "[And] to restore that ecosystem and to restore the habitat that is being degraded and lost through that fire-suppression effect."

To adapt to wildfire behaviour going forward, our highly altered landscapes will need improved forest management to create more resilient ecosystems, Daniels said.

"We have to do it in a way where we don't end up only with the highest severity fires that are impacting our landscapes today,” said Daniels. "To reduce the amount of fuels and to allow that good fire, the cooler and lower-intensity fires, to be part of the landscape is a critical next-step approach."

WATCH: How a major highway is trying to boost pollinator populations

Thumbnail contains images courtesy of BC Wildfire Service (left)/Twitter and Getty Images-1063980646 (right).

Follow Nathan Howes on Twitter.