'Feel' miserable out? Humidex and wind chill are calibrated to your body

Humidity makes heat worse, and wind makes a cold day frigid. There’s solid science behind the humidex and wind chill that take into account weather’s toll on our bodies

A searingly hot or bitterly cold day can have a significant impact on our bodies that goes far beyond a simple number on the thermometer.

Meteorology is a study of humans as much as it is a study of the weather itself. Every part of a meteorologist’s job—from tracking storms on radar to predicting tomorrow’s high temperature—is done with you and me in mind.

And everyday weather has no greater impact on our bodies than the simple combination of temperature, humidity, and wind. Humidity can make heat lethal. Wind on a cold day can cost you a finger—or worse.

Humidex, heat index, and wind chill are based on medical studies

A humid day in the middle of the summer can make a hot afternoon feel downright atrocious. 33°C under bright sunshine is rough enough when you’re not used to the heat, but throw in humidity, and it could easily feel like 40 or hotter.

The same goes for a cold winter day. Temperatures dipping below freezing is usually no sweat in a hearty country like Canada, but throw some gusty winds in the mix and your fingers can go numb in a hurry.

Scientists have spent decades studying how to best account for these factors when talking about temperatures. Those efforts brought about the heat index, the humidex, and wind chill, all metrics that we rely on just about every day.

Those findings allowed meteorologists to develop different values to take into account factors like humidity and wind to tell us how conditions really affect our bodies.

Humidity takes a serious toll on hot days

Hot temperatures are hard on the human body to begin with, but adding humidity to the air can make those steamy summer days a life-threatening prospect.

Air’s ability to hold moisture depends on its temperature. Hot air expands, leaving room for much more water vapour than denser, more compact cold air. That’s part of why it’s so much drier in the winter than it is in the summer.

We can measure air’s ability to hold water vapour with the dew point. The dew point is the temperature at which air would become fully saturated with water vapour, or reach 100 percent relative humidity. Lower dew points signal drier and more comfortable air, while higher dew point temperatures are indicative of sticky, muggy conditions.

Tracking the amount of moisture in the air is important because the human body uses evaporation to cool off. Sweat evaporating into the air pulls heat away from our skin, helping us regulate our body temperature when we’re overworked in warm conditions.

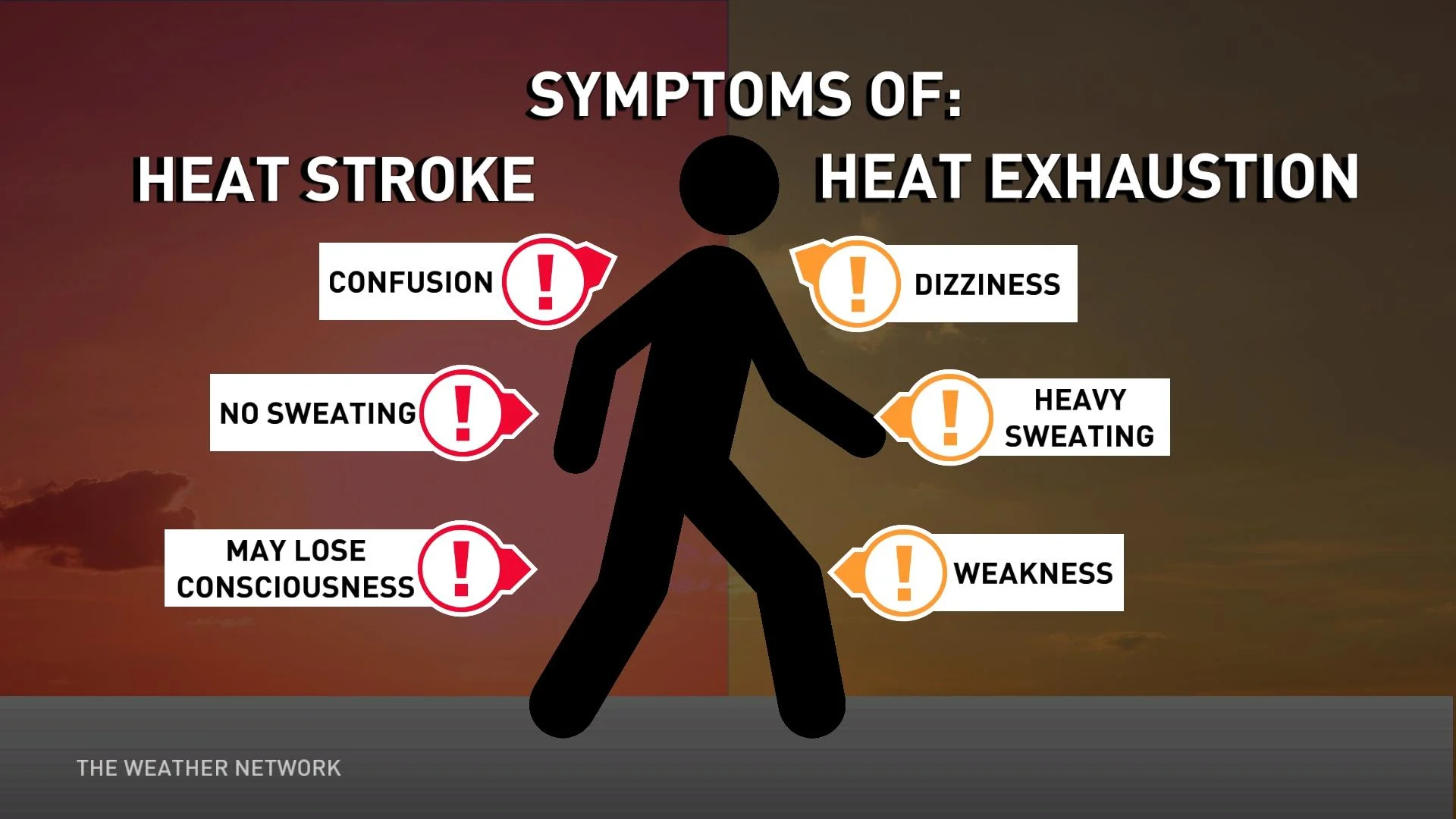

If there’s too much moisture in the air, our sweat won’t evaporate efficiently from our skin, hampering our ability to cool off when we get too hot. If it’s both really hot and really humid outside, the inability to cool down through sweat can lead to life-threatening heat illnesses.

WATCH: What longer, hotter, and more frequent heat waves means for your health

Humidex and heat index are closely related

You’ll sometimes hear different values to measure the combined effects of heat and humidity on our bodies. The heat index and humidex are the most common values. Heat index readings are common in the U.S. and around the world, while the humidex is a uniquely Canadian metric.

Scientists developed the heat index in the 1970s by conducting detailed studies to see how the human body reacted when exposed to different levels of heat and humidity. (If you’re really bored, you can read a detailed paper on it here from the U.S. National Weather Service.) They used their findings to estimate what it feels like to our bodies when it’s both hot and humid.

If it’s 95°F (35°C) with a relative humidity of 42 percent, the heat and humidity combined would make it feel like about 101°F (38°C). This means that your body would have to work as hard to cool you off on that muggy 35°C afternoon as it would if the temperature were really 38°C.

It may not seem like much, but that’s a fair amount of heat stress even for the fittest individuals.

Instead of using relative humidity, Canada’s humidex—short for humidity index—combines the air temperature and the dew point to estimate how our bodies react to muggy air.

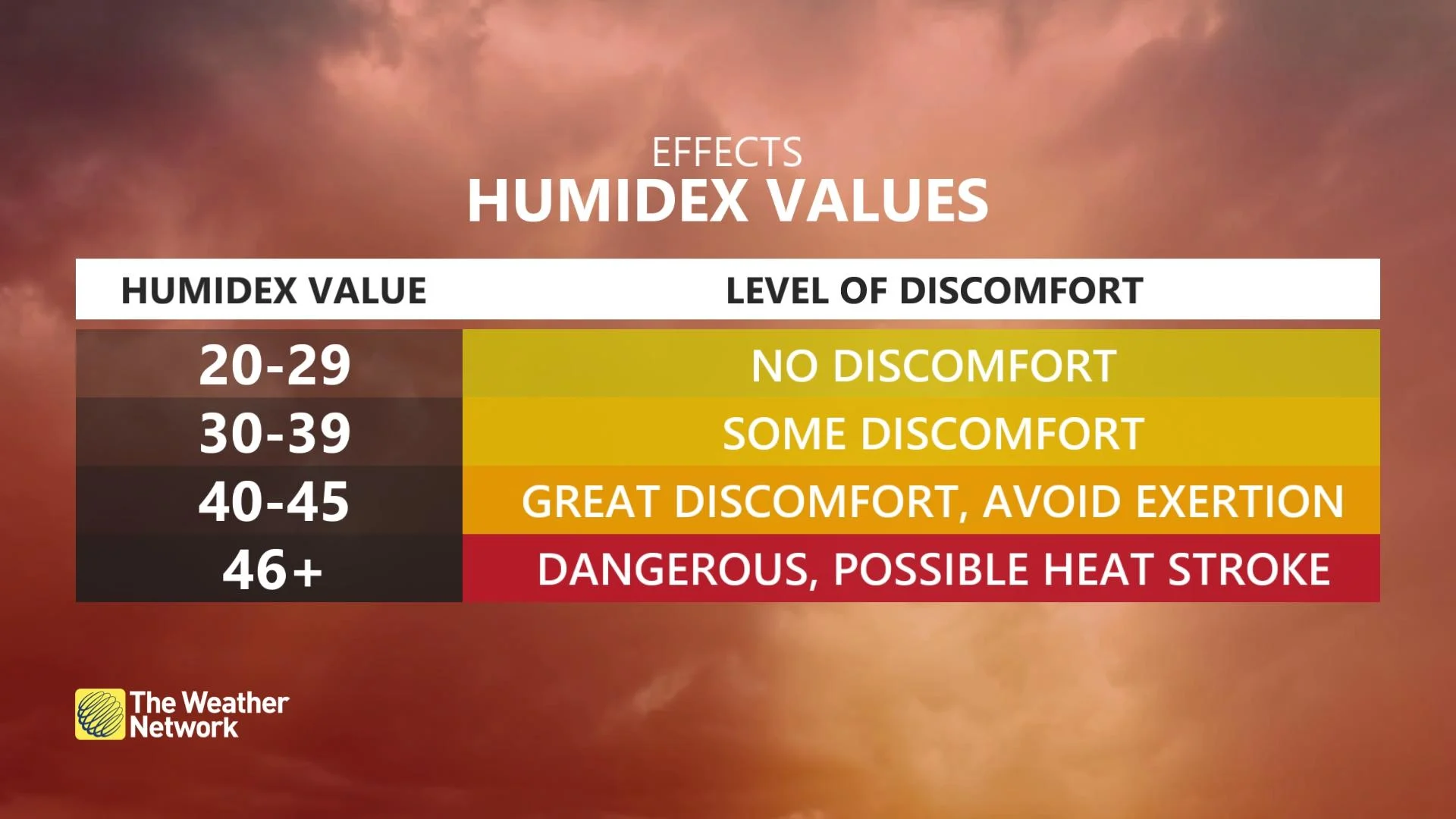

"Because it takes into account the two most important factors that affect summer comfort, it can be a better measure of how stifling the air feels than either temperature or humidity alone," Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) says of the humidex, which has been in use since the mid-1960s.

The humidex also uses a slightly different formula and slightly different assumptions about other factors like sunshine and clothing to arrive at a similar feels-like value.

On that same afternoon, if the air temperature is 35°C with a dew point of 20°C, the humidex reading would come out to 43—quite the tropical afternoon, and one in which anyone who overdoes it outdoors could fall ill with heat exhaustion or worse.

RELATED: How to spot a heat emergency and what to do

Wind chill values give us a countdown to frozen injuries

The opposite end of the extreme weather spectrum reveals the hidden dangers lurking on a frigid winter’s day.

Cold takes its own toll on the human body. One of the many ways we stay warm when it’s chilly outside is through our own radiant heat. Our body heat warms up the layer of air touching any exposed skin, which provides us with a little bit of insulation against the harsh chill.

When the wind blows, however, that tiny layer of insulation is stripped away, and the full force of the cold air presses directly against any exposed skin. The harder the wind blows, the more intensely that cold air rubs against our skin.

LEARN MORE: Understanding the warning signs of frostbite

Much like those summertime feels-like temperatures, scientists conducted medical studies to see how gusty winds affect the human body in cold temperatures. They used those findings to create the wind chill, which tells us what temperature it really feels like on exposed skin when it’s both cold and windy.

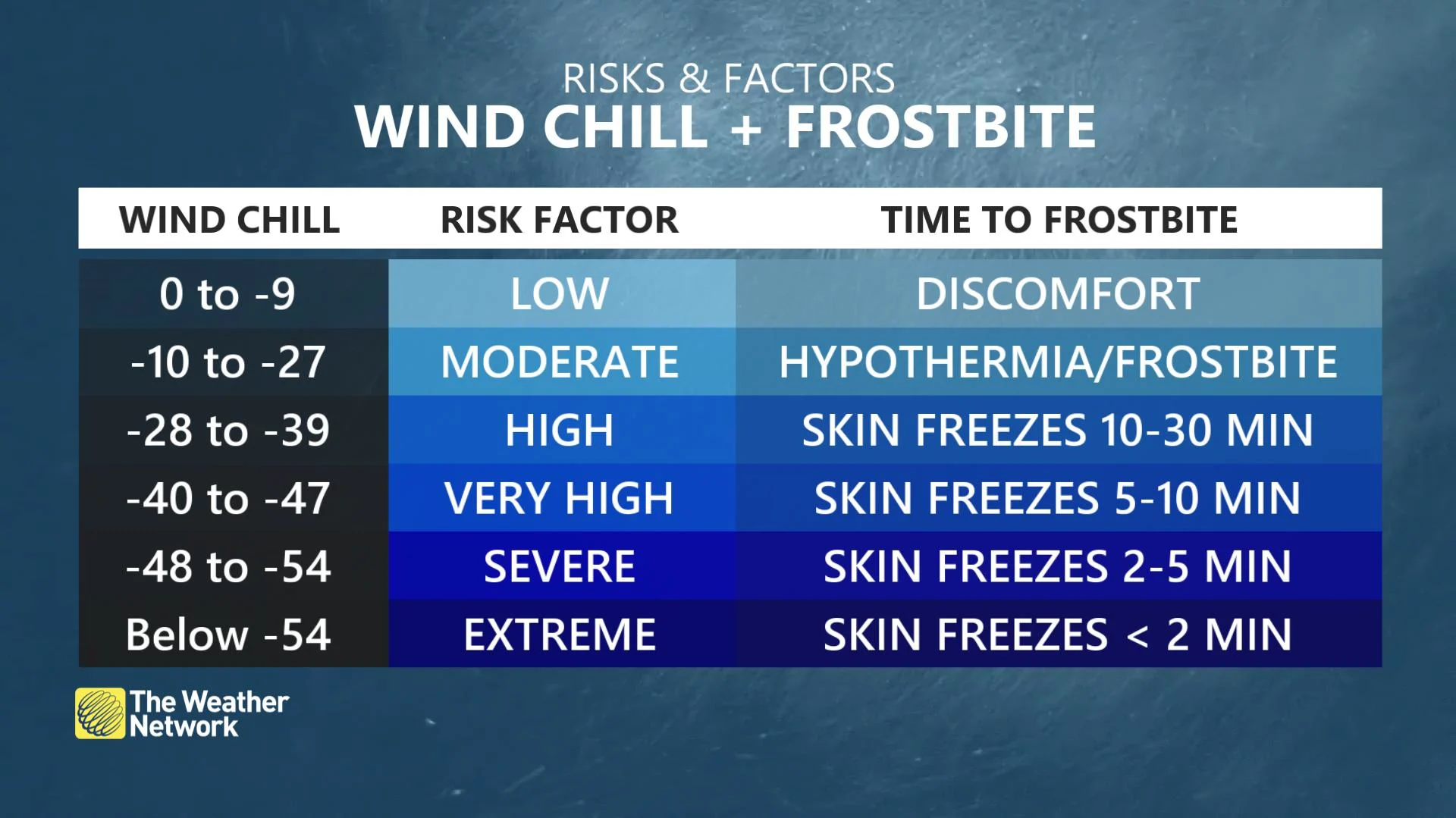

If the air temperature is -10°C and there’s a 15 km/h wind blowing—not uncommon on any winter day across Canada—the wind chill would make it feel like -17 to your body. And it only gets worse from there.

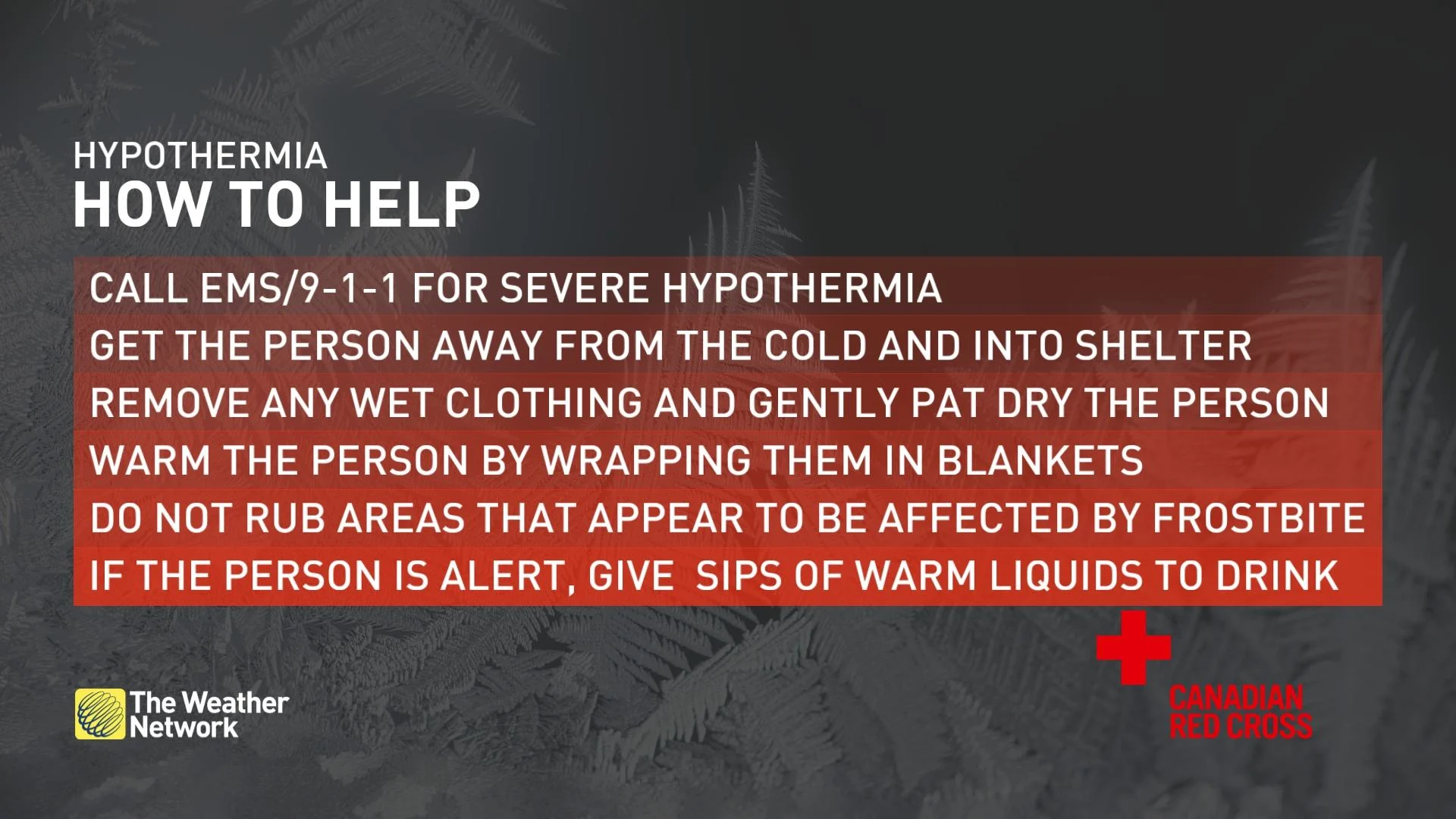

"The wind chill index allows Canadians to learn the best ways to avoid injuries from the cold," ECCC says. "This includes dressing warmly to avoid frostbite and hypothermia."

It’s not uncommon to see wind chill values plummet to -40 or beyond during a brutal winter storm, a time during which it’s dangerous to spend any amount of time outdoors with even a slight amount of exposed skin.

Frostbite, a serious condition in which exposed skin freezes, can develop in as little as 5 minutes during those brutal conditions. A potentially lethal case of hypothermia can set in not long after.

DON'T MISS: Why some people feel the cold more than others

Improvements may arrive in the years ahead

The humidex and wind chill are two ways that meteorologists look to boil complicated scientific data down to a bite-sized number that can help you plan your day and stay safe.

There are flaws in any estimated metric, of course. Working out in bright sunshine on a humid July day will take a much greater physical toll than digging in your shady garden, for instance, a factor that the humidex doesn’t take into account.

Meteorologists are always searching for better and more meaningful ways to relay information in ways that people can use to improve their lives.

One such way is a slow but steady transition to the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) during the summer months.

The WBGT uses the temperature in the sunshine, cloud cover, wind speeds, and other important weather data to provide a standardized value to judge the danger posed by hot and muggy conditions. This is especially useful for athletes, construction workers, and other folks who often spend extended periods of time outdoors on hot days.

Header image created using imagery from Unsplash.