Newfound exoplanet 'Proxima d' is one of the lightest ever discovered

"Our closest stellar neighbour seems to be packed with interesting new worlds," says one researcher.

Astronomers appear to have found a third planet orbiting our neighbouring star. This tiny world looks to be one of the lightest exoplanets ever discovered.

The closest star to the Sun, the red dwarf Proxima Centauri, may not be getting the attention and recognition it truly deserves. Located just over 4 light years away from us, this tiny star is only about one-eighth the mass of our Sun. Still, it looks to have a small collection of planets circling around it.

In 2016, astronomers working with the Pale Red Dot campaign spotted evidence for a rocky world there, just a bit larger and more massive than Earth. They named it Proxima b (the star is technically Proxima a). The planet takes roughly 11 days to orbit Proxima Centauri, and it is considered to be within the star's 'habitable zone' — the band of space around the star where it's possible for a planet to sustain liquid water on its surface.

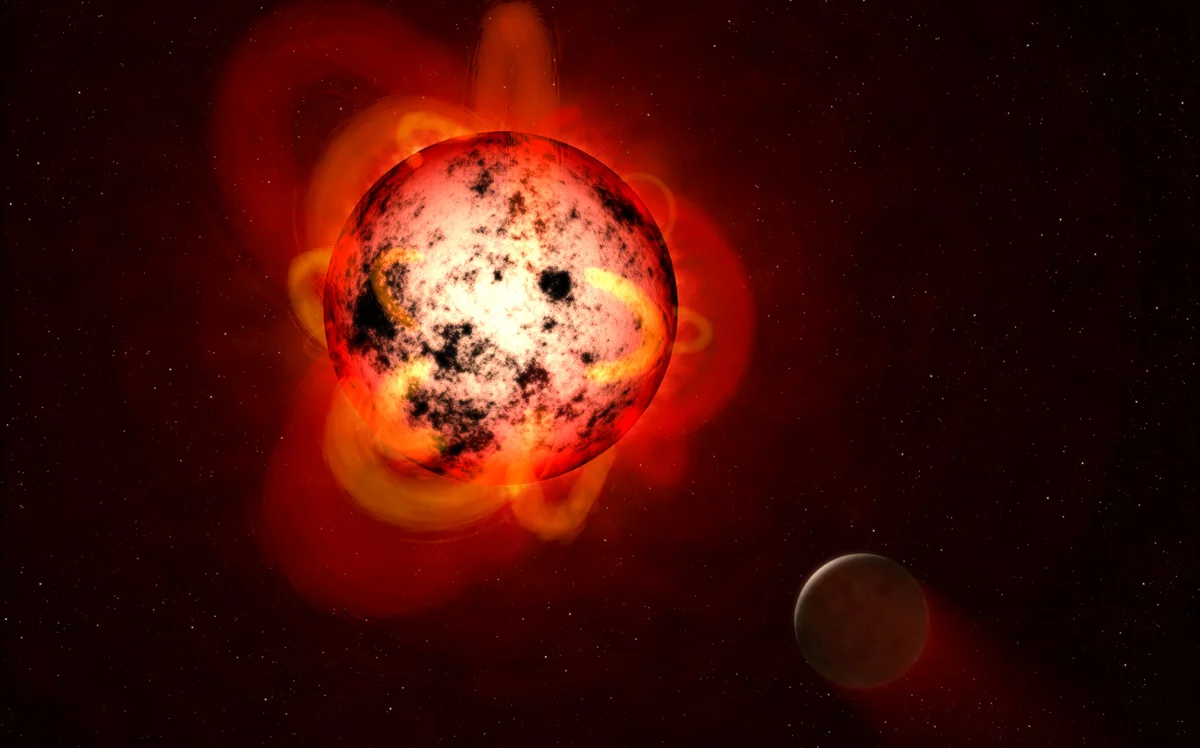

Red dwarf stars are notoriously active. So, that means that there's a fair chance that Proxima b has been rendered lifeless by intense solar flares. Still, this is the closest 'habitable zone' exoplanet to Earth.

This illustration shows an active red dwarf star circled by a hypothetical exoplanet. Credit: NASA/ESA/STScI/G. Bacon

A few years later, in 2019, evidence was found for a second planet, Proxima c. Several times more massive than Earth, it is probably a 'mini-Neptune', and it takes over 5 years to orbit its star.

In 2020, as astronomers with the European Southern Observatory used more sensitive instruments to confirm that Proxima b really did exist, their observations also revealed signs of yet another planet.

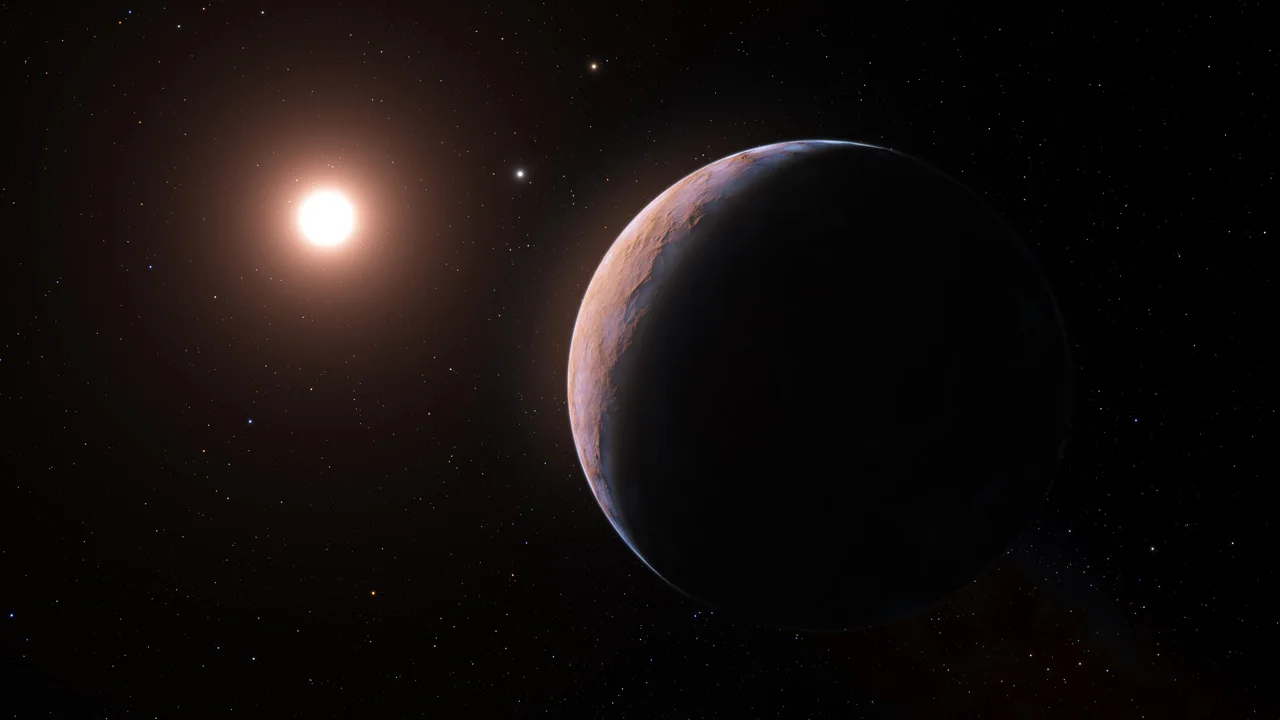

This artist's impression shows rocky Proxima d orbiting around red dwarf Proxima Centauri, located 4.3 light years away from Earth. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

This new discovery, now named Proxima d, orbits once every five days or so, meaning that it's even closer to its star than Proxima b. Also, it is small, with only around one-quarter the mass of Earth. That makes it one of the least massive planets discovered so far.

"The discovery shows that our closest stellar neighbour seems to be packed with interesting new worlds, within reach of further study and future exploration," João Faria, a researcher at the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences in Portugal, said in an ESO press release. The study that Faria led, which examined the evidence for Proxima d, was published this week in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

This discovery is remarkable because locating small exoplanets is very challenging.

If you're watching a star for 'transits' — where the star's brightness dims briefly as a planet passes in front of it — the signal from a small planet can be lost in the star's normal activity. The same goes for using the 'radial velocity' method, which was used to find Proxima d.

As a planet or system of planets orbits around a star, their gravity tugs on the star, causing it to 'wobble' slightly, back and forth. The lower the mass of the planet, though, the smaller the wobble it causes. So, unless you have an extremely sensitive instrument, you can miss the effects of a planet the size of Earth or smaller.

Watch below: How to find alien worlds using by watching for a wobble

Proxima d was spotted using an instrument called ESPRESSO, or the Echelle SPectrograph for Rocky Exoplanets and Stable Spectroscopic Observations, located at the ESO's Paranal Observatory in northern Chile. ESPRESSO just happens to be one of the most sensitive instruments ever built to detect the wobble of stars due to their planets.

According to the ESO, Proxima d's gravity only caused its star to wobble at a rate of around 40 centimetres per second, or 1.44 kilometres per hour. Detecting such a tiny shift from 40 trillion kilometres away is very impressive!

"This achievement is extremely important," Pedro Figueira, the ESO's ESPRESSO instrument scientist, said in the press release. "It shows that the radial velocity technique has the potential to unveil a population of light planets, like our own, that are expected to be the most abundant in our galaxy and that can potentially host life as we know it."