Friday night's Strawberry Moon may solve a Stonehenge mystery

A rare Full Moon 'lunistice' may reveal another celestial pattern tracked by the ancients who built Stonehenge.

Look up Friday night, to see the Full Strawberry Moon!

The first Full Moon of Summer 2024 rises on the night of June 21. Not only is this the first of four Full Moons we'll see during this season, it is also of special interest to astroarchaeologists studying the celestial cycles tracked by the builders of Stonehenge!

Visit our Complete Guide to Summer 2024 for an in-depth look at the Summer Forecast, tips to plan for it and much more!

What is a 'Strawberry Moon'?

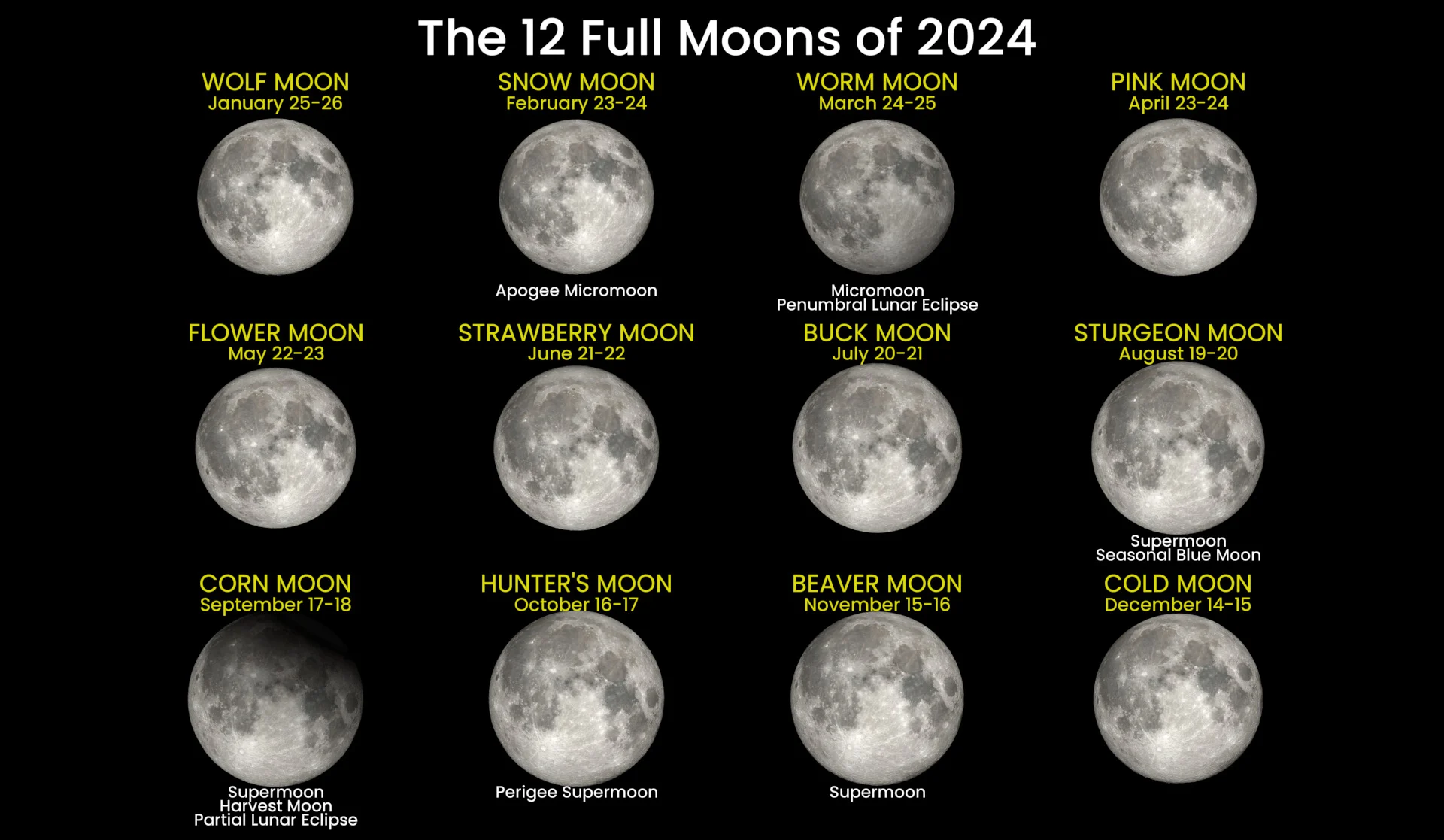

According to the Old Farmer's Almanac, each Full Moon of the year goes by several names, taken from the lunar calendars of First Nations people, or from Colonial and European folklore.

The popular name of the June Full Moon is the Strawberry Moon, as this was traditionally the time of year to pick ripened strawberries in what is now the northeastern United States.

This graphic collects all the relevant data about each Full Moon of 2024, including their popular name, whether they are a 'super' or 'micro' Moon, a 'perigee' or 'apogee' Full Moon, and if they are remarkable in some other way (Harvest Moon, lunar eclipse, etc.). (Scott Sutherland/NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio/Fred Espenak)

For those names borrowed from First Nations lunar calendars, they don't just refer to the Full Moon itself. They are actually the names of the 28-day periods that begin with each Full Moon. Thus, the Strawberry Moon in 2024 is the lunar month from June 21 through July 19.

Other names for the June Full Moon (and the lunar month following it) include Berries Ripen Moon, Birth Moon, Blooming Moon, Egg Laying Moon, Hatching Moon, Green Corn Moon, Hot Moon, and Hoer Moon.

Full Moon Lunistice

If you were to closely observe the Moon during its monthly cycle, besides the changing of its phase, you might notice two other things that change as well: exactly where on the horizon the Moon rises and sets, and exactly how high the Moon reaches in the sky.

These changes occur because the Moon's orbit is tilted, not only with respect to Earth's equator, but also compared to the plane of Earth's orbit around the Sun.

So, the tilt of Earth's axis causes us to see the Sun at both a highest and lowest point in the sky throughout the year, on the solstices. In the same way, the tilt of the Moon's orbit results in it having a highest and lowest point in the sky as well. These are known as lunar standstills or lunistices.

Now, the Moon experiencing a lunistice is actually quite common. Just as we see two solstices every time Earth goes around the Sun, we also see two lunistices every time the Moon goes around the Earth. Thus, there are roughly two every month, and they can occur during any phase of the Moon.

However, there are two types of extreme lunar standstills, each of which occur far less frequently.

This diagram shows the Earth and Moon orientations during major and minor lunar standstills. The cycle represented by this is called the Cycle of Regression of the Nodes. (Scott Sutherland, based on a diagram by 'Another Matt' on Wikimedia Commons)

As shown in the diagram above, a 'major' lunar standstill occurs when Earth's axis and the Moon's orbital axis are at their maximum tilt away from each other. This results in the Moon being at its highest or lowest 'declination' in the sky. For someone in the northern hemisphere, the Moon being at its highest declination in the sky means that it rises at its farthest northeasterly point along the horizon, reaches its highest point in the sky that day or night, and then sets at its farthest northwesterly point along the horizon. At its lowest declination, it will rise and set at its lowest points along the horizon and reach its lowest point in the sky in between.

On the other hand, a 'minor' lunar standstill is when the Moon's orbital axis is oriented the same as above, but Earth's axis is rotated 180 degrees from that scenario. Thus, the Moon still rises and sets at a minimum or maximum for that period of time, but at a smaller angle than during a major standstill (around 18.3 degrees instead of 28.5 degrees).

This diagram shows the range of moonrises during a major and minor lunar standstill. (Fabio Silva/The Conversation, CC BY-NC)

Major lunar standstills occur once every 18 years or so, as the Sun's gravity causes the Moon's orbit to slowly 'wobble' around Earth. Minor lunar standstills occur around the midpoint between one major lunar standstill and the next. Also, the very slow precession of the Moon's orbit around Earth means that it takes us some time to pass through one of these events. As such, the major lunar standstill we are about to experience will actually last throughout the rest of 2024 and 2025.

However, on the night of June 21-22, 2024, we are going to see a somewhat more rare instance of this phenomenon: a Full Moon major lunar standstill that occurs very closely aligned with the summer solstice.

The Moon will rise at its farthest southeasterly point that night, reach its lowest point in the night sky, and set at its farthest southwestern point the following morning.

A Stonehenge mystery

The timing of this southernmost major lunar standstill may help researchers solve a mystery about Stonehenge, the famous megalith located on Salisbury Plain, in the county of Wiltshire, in the south west of England.

Stonehenge is well known for how it closely tracks the motions of the Sun in the sky. For centuries, people have gathered there to see the rising Sun line up with the ancient stones on the summer solstice, and the setting Sun align with the structure on the winter solstice.

Within the past 60 years, though, some researchers have begun to wonder if Stonehenge was built with the motions of the Moon in mind, as well. Specifically, they've been asking if the layout of specific stones surrounding the main circle — the Station Stones — are positioned to align with moonrise and moonset during a major lunar standstill.

This diagram of the layout of Stonehenge features the rectangle that links the Station Stones (the two existing stones and the two locations that are known to have once held similar stones), which may have a lunar connection. (Adapted from Astroskiandhike/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

"The strongest evidence we have for people marking the major lunar standstill comes from the US southwest," Fabio Silva, Amanda Chadburn, and Erica Ellingson wrote in an article on The Conversation in April 2024. Silva and Chadburn are both researchers in the field of archaeology at Bournemouth University in the U.K., while Ellingson is a professor emeritus in astrophysics at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"The Great House of Chimney Rock, a multi-level complex built by the ancestral Pueblo people in the San Juan National Forest, Colorado, more than 1,000 years ago," they explained. "It lies on a ridge that ends at a natural formation of twin rock pillars — an area that has cultural significance to more than 26 native American tribal nations. From the vantage point of the Great House, the Sun will never rise in the gap between the pillars. However, during a major standstill the Moon does rise between them in awe-inspiring fashion."

The researchers believe that if one culture made these kinds of observations, others may have as well, including those who built Stonehenge. Specifically, ancient cremated human remains were found buried near the southeast part of the megalith, which apparently aligns with the southernmost major lunar standstill moonrise.

With the onset of this new major lunar standstill, the researchers plan to observe these potential alignments, two of which should occur every month from February 2024 through November 2025.

The English Heritage website is hosting a live stream of the southernmost moonrise from Stonehenge, starting at 4:30 p.m. EDT on Friday, June 21.

"The major lunar standstill hypothesis, however, raises more questions than it answers," Silva, Chadburn, and Ellingson wrote. "We don't know if the lunar alignments of the station stones were symbolic or whether people were meant to observe the Moon through them. Neither do we know which phases of the Moon would be more dramatic to witness."

Thumbnail image is a 'double exposure' of the Harvest Moon and Stonehenge taken on the night of October 6, 2017, courtesy Jeff Welch on Flickr (CC BY 2.0). The image presents both the Moon and the monument at their best exposure, something that would be difficult to achieve with a single photograph.