NASA telescope spots molecular water on the sunlit Moon surface

"Without a thick atmosphere, water on the sunlit lunar surface should just be lost to space. Yet somehow we're seeing it."

Using NASA's airborne SOFIA telescope, a team of researchers has confirmed that even in daylight, there may be abundant water on the surface of the Moon.

Over the years, scientists have found many hints that there could be vast resources of water available on the Moon. Most of the lunar water we know about is locked away as ice in frigid, perpetually-shadowed polar craters. This is especially true near the Moon's south pole, and there is a clear focus on exploring this region of the lunar surface.

There have been indications that sunlit parts of the Moon could also have water. Observations have shown hints, but there was always a problem. The researchers didn't know exactly what they were seeing.

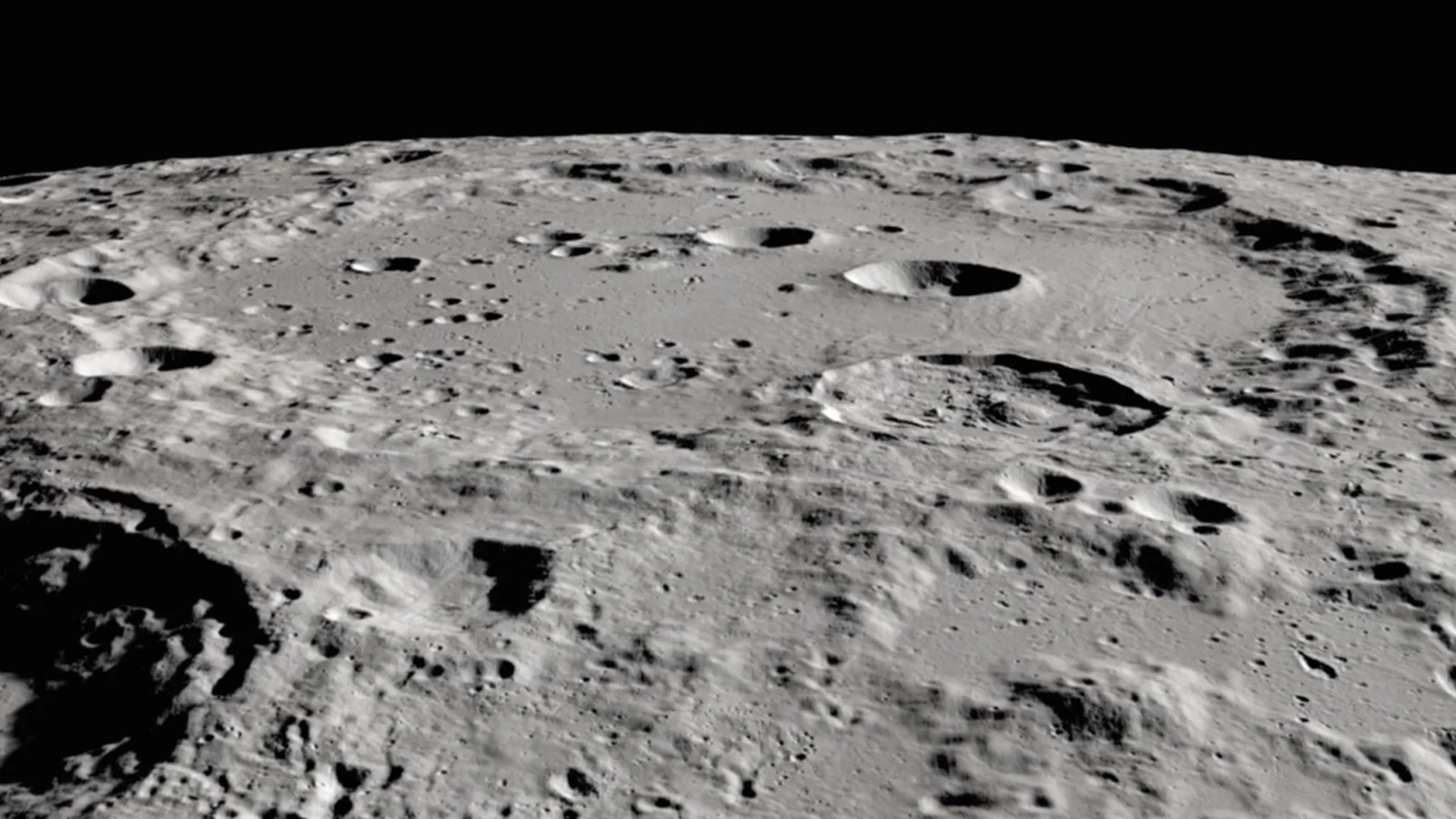

Clavius Crater, near the Moon's south pole, is the second largest lunar crater visible from Earth. Credit: NASA

"Prior to the SOFIA observations, we knew there was some kind of hydration," Casey Honniball, the lead author of the new study from the University of Hawaii at Mānoa in Honolulu, said in a NASA press release. "But we didn't know how much, if any, was actually water molecules — like we drink every day — or something more like drain cleaner."

Telescopes that collected these hints of water before this study were simply detecting the presence of hydrogen. This hydrogen may have been part of an actual water molecule — H2O. It was just as likely, however, that it could have been part of another molecule — OH — known as 'hydroxyl'. There was no way, at the time, to distinguish between the two.

RELATED: LOOK UP! HALLOWEEN WILL BE EXTRA SPOOKY THIS YEAR

Telling the difference between them is really important, though. If it's water, that counts as a valuable resource for lunar exploration. It would be readily available for astronauts to dig up, purify, and drink! If it's hydroxyl, though, after expending considerable effort to separate it from the minerals it was locked up in, they'd only have something they could use to clean the Moon base.

Using SOFIA, NASA's Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, Honniball and her colleagues were able to observe wavelengths of infrared light that can distinguish between water and hydroxyl. So, they found a way to confirm, one way or the other, what previous efforts had detected. Aiming SOFIA at Clavius Crater, near the south pole of the Moon, the telescope confirmed that there was indeed water — H2O — on the surface there.

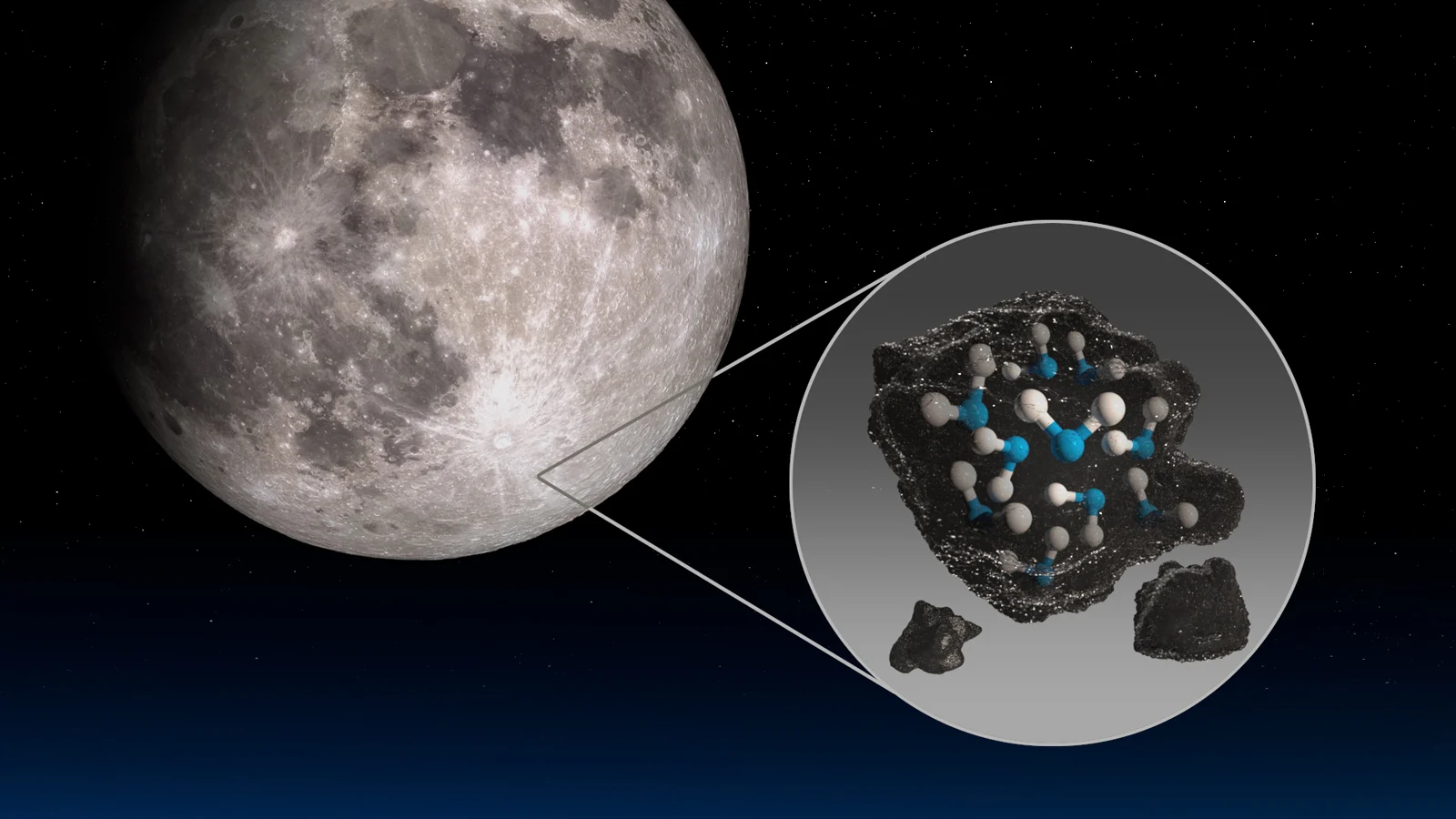

This artist's impression shows the detection of water in the Moon's Clavius Crater, with an illustration depicting water trapped in the lunar soil there. Credit: NASA

This discovery that water is not only confined to frigid polar craters is a surprising one.

"Without a thick atmosphere, water on the sunlit lunar surface should just be lost to space," Honniball, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said in the press release. "Yet somehow we're seeing it. Something is generating the water, and something must be trapping it there."

It's not known, yet, exactly where this water is. It could simply be trapped between grains of soil, or embedded in tiny glass beads produced by meteor impacts, or a combination of both. From this study, though, for every cubic metre of lunar soil we gathered up from Clavius Crater, we could extract roughly a 12-ounce bottle of water. According to NASA, that's 100 times less than you could get from the Sahara desert.

For SOFIA, a telescope that flies inside of a modified 747 jet airliner, at heights of up to 45,000 feet, this was the first time it was used to take observations of the Moon. Apparently, it will not be the last.

"It's incredible that this discovery came out of what was essentially a test," said Naseem Rangwala, SOFIA's project scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center, "and now that we know we can do this, we're planning more flights to do more observations."