NASA's Parker Solar Probe becomes first spacecraft to 'touch' the Sun

Diving closer to the Sun then ever before, the NASA probe returned new insights about our home star.

After plunging itself through the edge of the solar corona back in April, NASA's Parker Solar Probe effectively 'touched' the Sun, becoming the first spacecraft to ever come that close to our host star.

The Parker Solar Probe has been in space for over three years now. Its mission is to orbit the Sun, drawing closer and closer to the star while sending back data from the array of sensors installed on board. The objective is to help scientists solve persistent mysteries about solar activity and the Sun's atmosphere. Also, since it is going where no spacecraft has ever gone before, it will likely discover new secrets to explore.

One of the biggest mysteries about the Sun, so far, is the actual size of its atmosphere — the solar corona. Satellites in space continually watch the Sun and its corona, and we see the corona each time there is a total solar eclipse. However, these observations have not provided us with enough to know precisely how far the corona extends away from the Sun's surface (the photosphere).

The corona shines during a solar eclipse, as the Moon completely blocks the direct light from the Sun. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

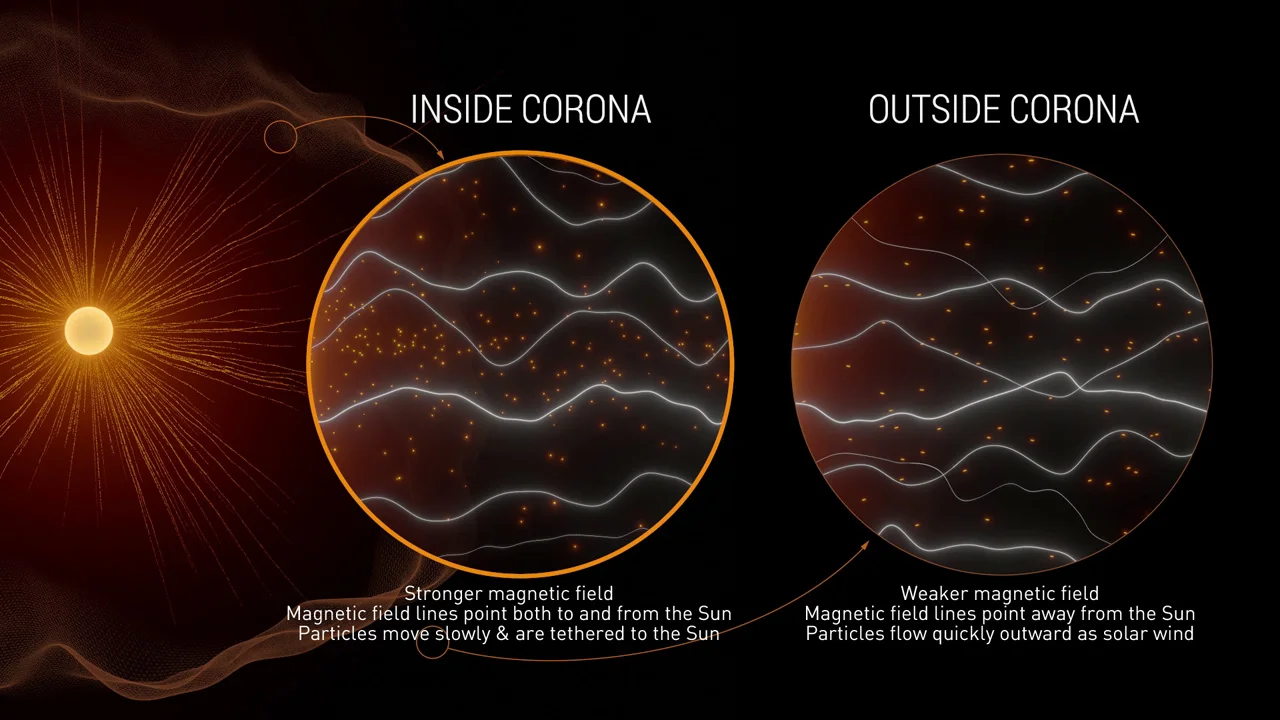

According to NASA, the best estimates put the edge of the corona — known as the Alfvén critical surface — anywhere from 6.8 million to 13.7 million kilometres out, or roughly 10 to 20 times the Sun's radius. Outside of that surface, solar particles move so quickly that they escape the Sun's gravity and become part of the solar wind. Inside the surface, though, particles are still bound to the Sun.

Before the Parker Solar Probe, no spacecraft had ever gotten close enough to see this boundary. However, as of the Probe's eighth pass around the Sun, on April 28, 2021, we finally have a much better idea of how big the corona really is.

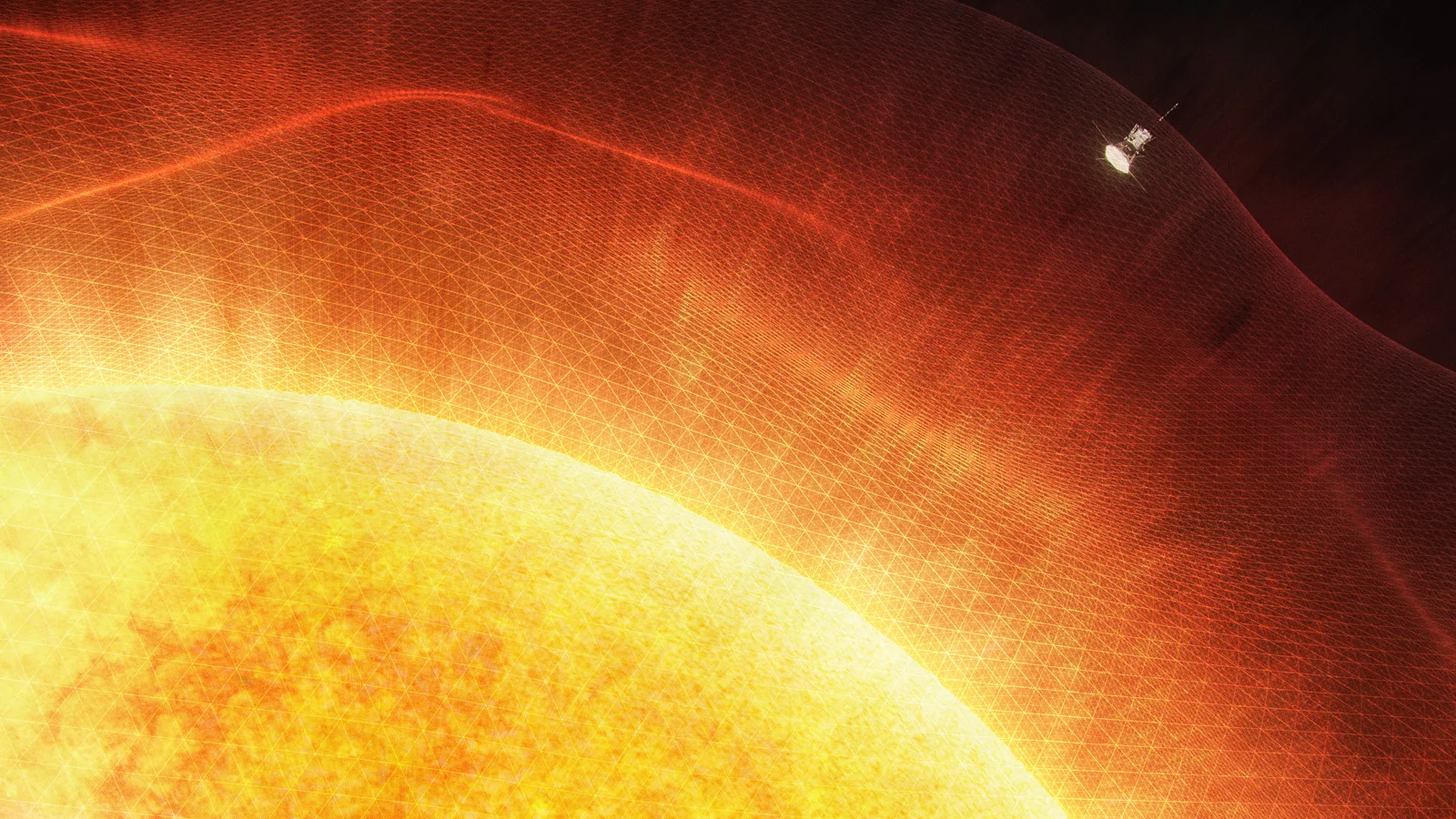

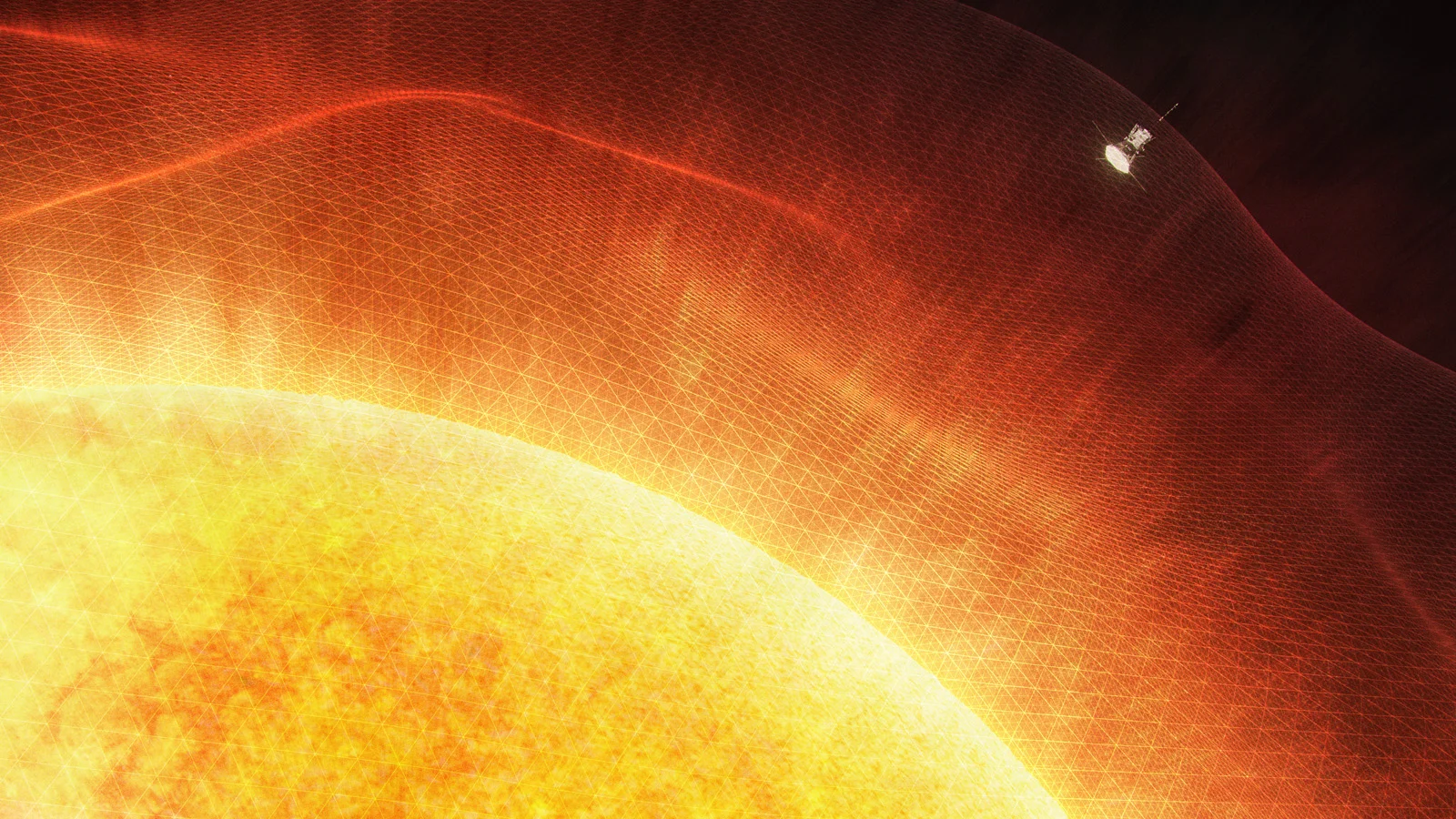

This illustration shows the Parker Solar Probe passing through the outer edge of the corona on April 28, 2021. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

On that orbit, the Probe made its closest flyby (aka 'perihelion') of the mission up until that time. Coming to within 10.4 million kilometres of the Sun, the spacecraft set a new distance record. At the same time, it also set a new speed record for space travel, as it whipped around the Sun at 532,000 kilometres per hour.

As PSP closed in on those records, though, it passed a distance of 13 million km from the surface (or around 18.8 solar radii) and recorded an abrupt change in the conditions around it. The particles of the solar wind that were whizzing past on their way out into the solar system suddenly gave way, and it was instead surrounded by a much stronger solar magnetic field and by solar particles that were moving much more slowly.

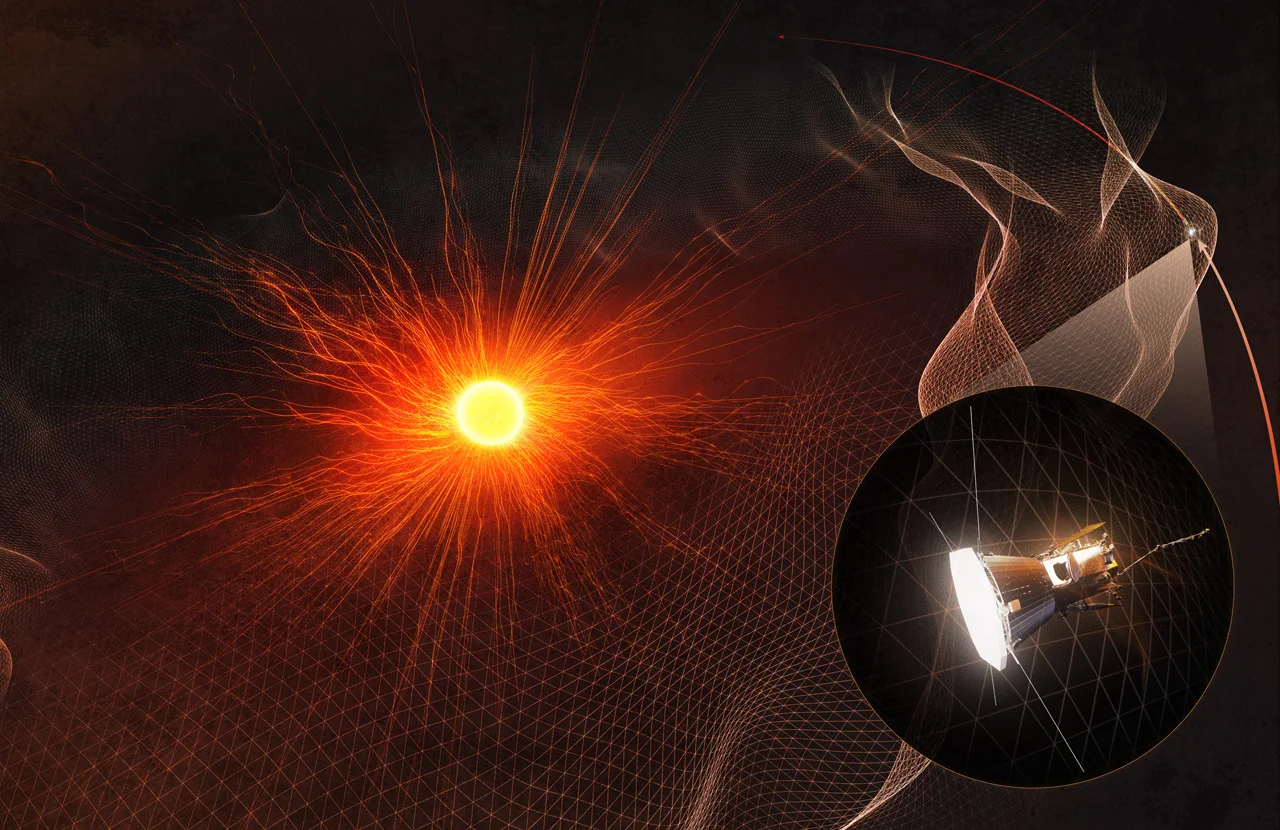

Parker Solar Probe data from its April 2021 perihelion revealed that the spacecraft finally plunged through the Sun's corona. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

From this, the mission scientists determined that the Probe had, indeed, finally flown through a portion of the corona. It, effectively, 'touched' the Sun for the first time. Even more, as the spacecraft made this passage, it actually flew into and out of the corona several times, revealing the corona's edge to be wrinkled with spikes and valleys.

"Flying so close to the Sun, Parker Solar Probe now senses conditions in the magnetically dominated layer of the solar atmosphere — the corona — that we never could before," Nour Raouafi, the Parker project scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, said in a NASA press release.

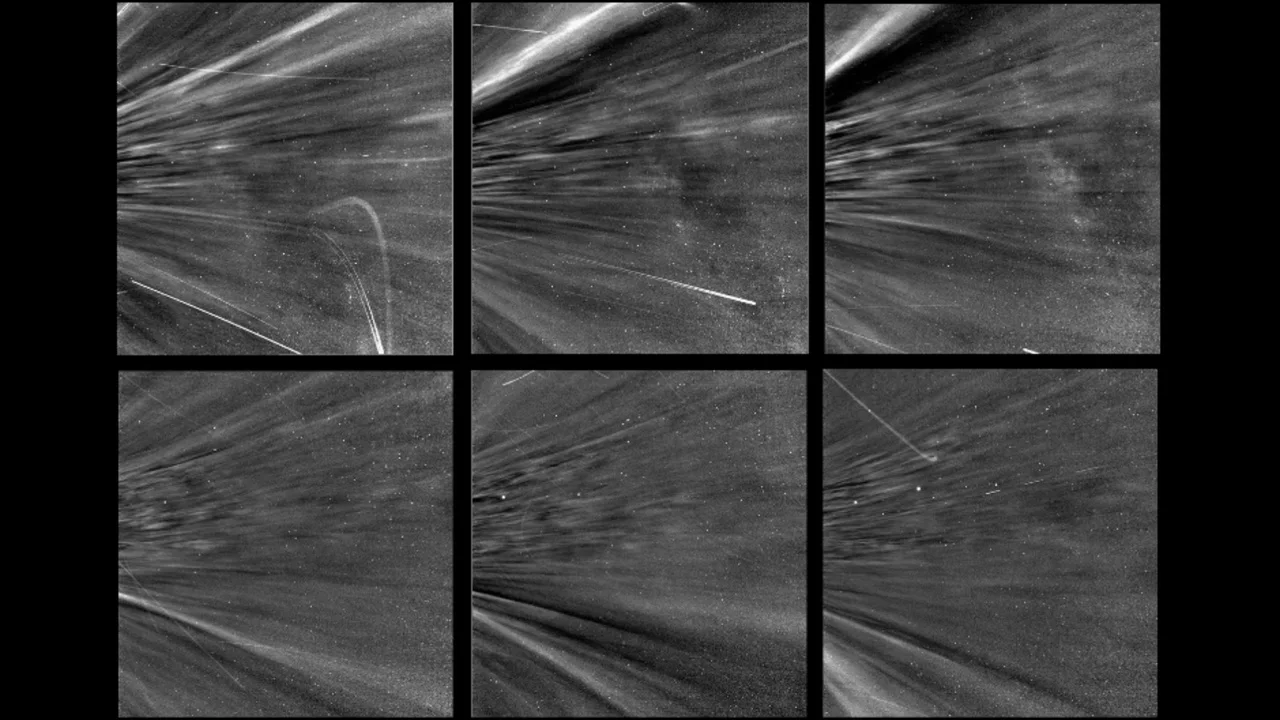

"We see evidence of being in the corona in magnetic field data, solar wind data, and visually in images. We can actually see the spacecraft flying through coronal structures that can be observed during a total solar eclipse."

The coronal structures that Dr. Raouafi refers to are known as coronal streamers or pseudostreamers.

On the Parker Solar Probe's second pass through the corona, on perihelion 9, the spacecraft flew by structures called coronal streamers — the bright features moving upward in the upper images and angled downward in the lower row. PSP could only capture such images from within the corona, and this is the first time they have been observed this closely. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Naval Research Laboratory

According to NASA: Passing through the pseudostreamer was like flying into the eye of a storm. Inside the pseudostreamer, the conditions quieted, particles slowed, and number of switchbacks dropped — a dramatic change from the busy barrage of particles the spacecraft usually encounters in the solar wind. For the first time, the spacecraft found itself in a region where the magnetic fields were strong enough to dominate the movement of particles there. These conditions were the definitive proof the spacecraft had passed the Alfvén critical surface and entered the solar atmosphere where magnetic fields shape the movement of everything in the region.

Following the April pass through the corona, Parker Solar Probe has already made two more perihelion passes around the Sun — in August and November. As of that November pass, the 10th of the mission, it broke all previous records for flight speed and proximity to the Sun. Until June of 2023, the mission team will keep the spacecraft in its current orbit. This will allow the Probe to make another six passes around the Sun before it plunges even closer.

Parker Solar Probe passes along the edge of the corona in this illustration. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

The mission will gather even more data on the corona in that time. It will even have the chance to plumb deeper into the solar atmosphere.

In December of 2019, a new solar cycle began. Solar activity reached a minimum and is now ramping towards a new maximum around 2025. As activity increases, with more sunspots, solar flares and coronal mass ejections, this will cause the edge of the corona to expand outward. Thus, even as it maintains the same orbit for the next year and a half, the corona will expand around the Parker Solar Probe.

"I'm excited to see what Parker finds as it repeatedly passes through the corona in the years to come," Nicola Fox, the director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA HQ, which specializes in the study of the Sun and how its activity affects Earth and the solar system, said in the press release. "The opportunity for new discoveries is boundless."