Scientists find out what causes these strange 'spiders' on Mars

The peculiar, spindly features were long suspected to be seasonally-related, but a team in Ireland found a way to test that hypothesis.

Despite its many visits by probes and rovers, distant Mars still holds many secrets – though new research looks likely to have unlocked one of its more peculiar ones.

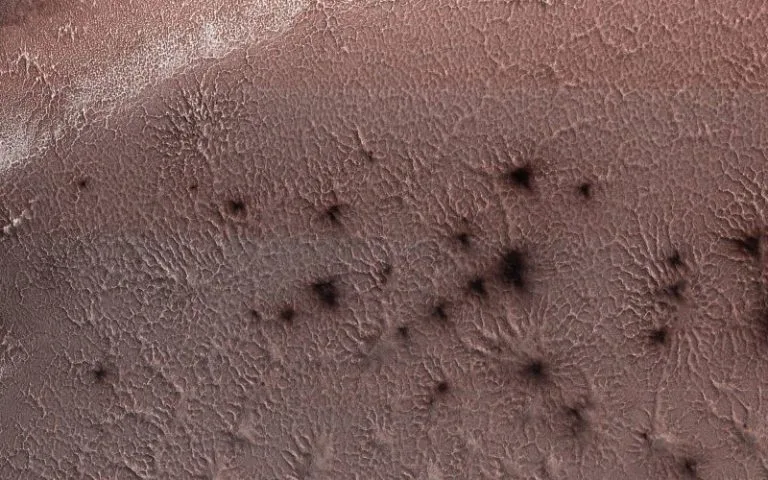

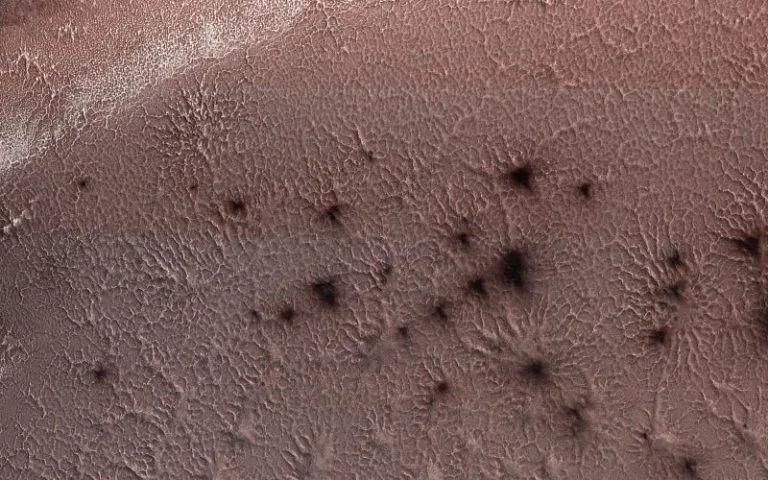

For several years, strange spider-like formations have been visible on the surface from orbit, dark and spindly against the planet's red deserts. Called 'araneiforms' by scientists, their location near Mars' south pole has led to theories that their formation was seasonally influenced.

Now, using a special lab designed to simulate conditions on the Martian surface, researchers in Ireland have confirmed the structures are formed when frozen carbon dioxide – also called 'dry ice' meets the warmer Martian soil.

The strange features, several of them hundreds of feet across, have been spotted from orbit for the past two decades. Image: NASA/Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

Unlike water ice, carbon dioxide typically does not 'melt,' in the sense of changing to a liquid state. Instead, it goes directly from a solid to a gaseous state, a process known as sublimation.

In the case of those Martian spiders, scientists had hypothesized that when sunlight hits Mars' CO2 ice, it heats up the soil beneath it, causing the ice at the base to sublimate, slowly building up pressure until the ice cracks. At that point, the built-up gas escapes, with a force that erodes those spindly patterns in the sand.

However, concrete evidence wasn't on hand until the Trinity study, which involved building a special chamber that could be sealed and pressurized to match Mars' temperature levels and very thin atmosphere. The scientists lowered blocks of dry ice with holes drilled in them and studied the escape of the sublimating gases, noting the patterns left behind in the soil below, which were similar to those observed on Mars from orbit.

"It is exciting because we are beginning to understand more about how the surface of Mars is changing seasonally today," lead researcher Dr. Lauren McKeown said in a release from Trinity University.

The researchers say their method can be used to study other geomorphic effects of dry ice sublimation on Mars, or even on other solar system bodies such as Enceladus or Europa with little or no atmosphere.

The team's findings were published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports.