UBC student discovers 17 alien worlds. One may be capable of hosting life!

UBC student Michelle Kunimoto is becoming a veteran planet hunter

Whether you're a professional astronomer or a citizen scientist, discovering just one alien planet (or 'exoplanet') is exciting, but how about 17 of them! Michelle Kunimoto, a PhD student in the University of British Columbia's Physics and Astronomy program, has done just that. Even more amazing, one of these potential alien worlds also has the potential to harbour life!

In a new study, published in The Astrophysical Journal last week, Kunimoto reports the discovery of these 17 'exoplanet candidates', along with her UBC PhD advisor Jaymie Matthews, and Henry Ngo from the National Research Council's Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Center.

She made this discovery by filtering the immense amount of data collected by NASA's Kepler Space Telescope through a special program known as a 'pipeline'. The hope was that this pipeline would spot the signals of exoplanets (known as 'transits'), and specifically catch ones that other automated processes, and even the human eyes of citizen scientists, had missed.

"Every time a planet passes in front of a star, it blocks a portion of that star's light and causes a temporary decrease in the star's brightness," Kunimoto said in a UBC press release. "By finding these dips, known as transits, you can start to piece together information about the planet, such as its size and how long it takes to orbit."

Michelle Kunimoto is a PhD student at the University of British Columbia's Physics and Astronomy department. Credit: UBC

The pipeline not only spotted most of the planets that had already been found by other methods, but it also picked out 17 more that hadn't yet been spotted, due to the very weak signals they produced.

"All of my new candidates are considered 'low signal-to-noise-ratio' (low SNR) candidates," Kunimoto said in an email. "Essentially, they are right near the detection limit of my search and produce very weak signals in the data."

While some of the stars Kepler viewed had very steady brightness, making it fairly easy to see the dip in brightness during a transit, many of them were very noisy. They changed brightness very quickly and randomly, perhaps due to having active surfaces with flares and sunspots, or due to something going on within the star. This makes it difficult to pick out the dips in brightness from small planets.

A SPECIAL ONE

This artist's impression shows the Kepler Space Telescope spotting distant planets transiting across the face of their star. Credit: NASA

One of the potential planets Kunimoto's pipeline found - named KIC-7340288 b - is around a star roughly 1,000 light years away from us, and it could be a special one.

According to Kunimoto, the first signal from KIC-7340288 b shows up within the first few hundreds of days of Kepler's mission, back in 2009, and the telescope recorded nine different transits from this potential planet.

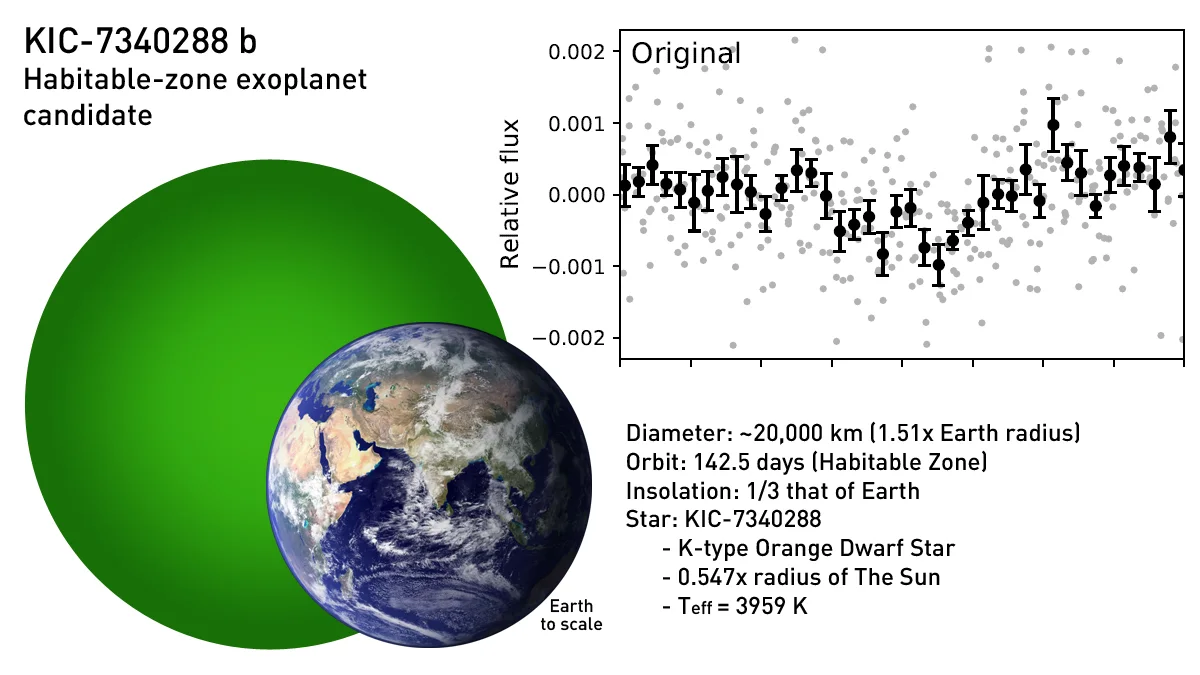

If it is real, this exoplanet appears to be roughly 1.5 times the size of Earth, with an orbit that takes it around its star once every 142.5 days.

This diagram shows the parameters of exoplanet candidate KIC-7340288 b, along with its Kepler light curve (note how noisy the data is!) and a comparison with Earth. Credits: Kunimoto, et al (2020)/Scott Sutherland

At that size, this 'super-Earth' could have a rocky surface, similar to Earth's, rather than being a gassy planet like Neptune.

Also, since it orbits an orange dwarf star, about half as big as the Sun, KIC-7340288 b's 142.5-day orbit would put it within its star's habitable zone - the region around the star where it is warm enough for liquid water to exist on a planet's surface.

That means if the right conditions exist there, otherwise - it has a reasonably thick atmosphere and a strong planetary magnetic field, and there was enough ice floating around the star so that water could collect on the planet as it developed - there's a possibility, however remote, that KIC-7340288 b could be teeming with life!

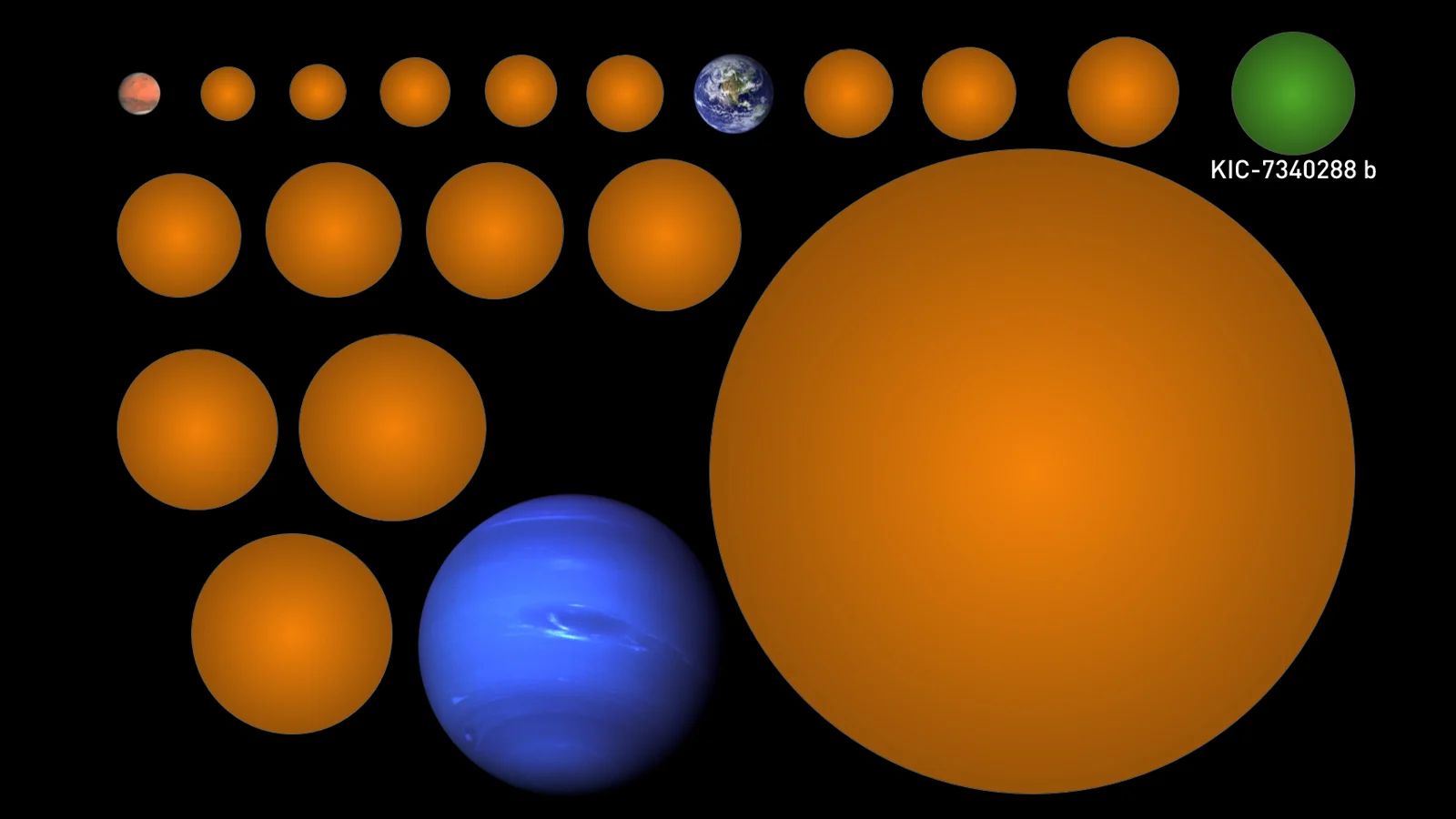

The 17 exoplanet candidates found by Michelle Kunimoto are represented here, alongside Mars, Earth and Neptune for size comparison. KIC-7340288 b is shown in green. Credit: Michelle Kunimoto

LOOKING FOR TRANSITS

During Kepler's nearly 10-year mission in space, it discovered thousands of potential planets orbiting distant stars, simply by holding very still and focusing exceptionally sensitive cameras on those stars. When it caught a star dimming, this would be flagged as a transit.

WATCH BELOW: LIKE KEPLER, NASA'S NEWEST EXOPLANET HUNTER WILL LOOK FOR TRANSITS

If the telescope sees this happen more than once for the same star, with the same dip in brightness and at regular intervals, the evidence grows stronger for it being due to a planet. If it spots different dips with different intervals, there could be more than one planet around that star.

Any signals Kepler saw during its mission simply noted 'candidate' exoplanets, however. There were several ways that a star can behave that might result in the signal of a transit. So, when a candidate was spotted, another telescope would have to observe that same star, to confirm that what Kepler saw was real. Anything that passed this test became a 'confirmed' exoplanet.

To date, Kepler has spotted 4,776 planet candidates, with 2,356 now confirmed. The rest await astronomers getting enough time on other telescopes to verify their existence. Of those confirmed, only a small number have any chance of being 'Earth-like'.

"This is a really exciting find, since there have only been 15 small, confirmed planets in the Habitable Zone found in Kepler data so far," Kunimoto told UBC News.

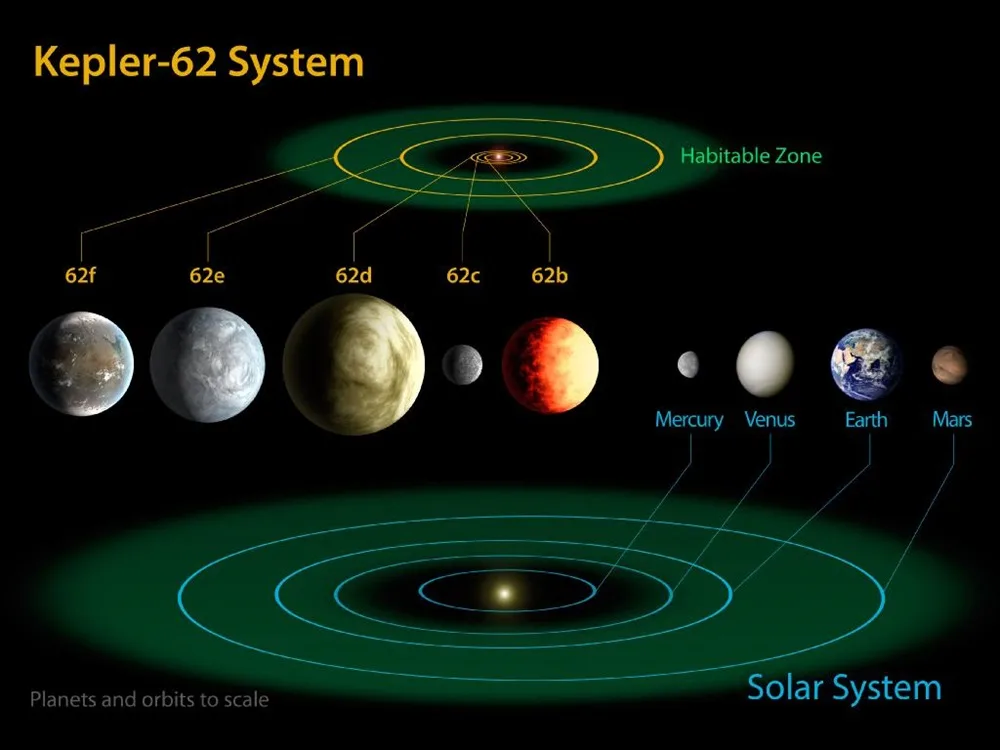

This diagram shows a sample exoplanet star system, named Kepler-62, compared to the orbits and sizes of Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. The green areas mark each star's habitable zone. Kepler-62's habitable zone is much closer to the star, due to the star being a small red dwarf, roughly two-thirds the size of the Sun. NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech

Just because a confirmed exoplanet orbits within its star's habitable zone, however, that does not mean that it is guaranteed to be friendly for life as we know it.

Some planets aren't lucky enough to form in a star system with an abundance of water available. Some planets never form an atmosphere, or they circle very active stars that strip away their atmosphere early on. Others develop an atmosphere so thick that it smothers any potential for advanced life.

One factor that is very important is the type of star the planet orbits. While active red dwarf stars may create a very hostile environment for their planets, we have ample evidence that Sun-like stars are much more friendly to theirs. Discovering how many small, rocky exoplanets exist around these friendlier stars may be the key to discovering alien life, and Kunimoto's PhD advisor is currently on the case.

"We'll be estimating how many planets are expected for stars with different temperatures," Matthews told UBC News. "A particularly important result will be finding a terrestrial Habitable Zone planet occurrence rate. How many Earth-like planets are there? Stay tuned."