In Fiona's wake, coastal residents desperate for extreme-weather solutions

When post-tropical storm Fiona hit the coast, Tim Borlase watched the storm surge lap up against his front doorstep and stop mere centimetres from flooding his cottage.

The property owner in Pointe-du-Chêne, a community on New Brunswick's southeast coast, knows a day could come when people will have to leave their land forever.

SEE ALSO: Fiona debris fuelling concerns about a summer of forest fires on P.E.I.

"It may be the case that at least my area, which is very low, may ultimately have to give in to climate change," he said.

The low-lying area, now part of the town of Shediac, has been filled with seasonal cottages and some year-round homes for more than a century. But an eroding shoreline and recent extreme weather are forcing people to re-evaluate their options.

Pointe-du-Chêne experienced major flooding after storm surges in 2000, 2010, during Dorian in 2019, and most recently with post-tropical storm Fiona.

Residents are also left with limited financial protection. The New Brunswick government recently announced it is capping financial disaster relief at $200,000 per property.

Before the changes, the maximum single payout was $160,000. But property owners could make multiple claims from damages year after year from the same type of disaster. Now, a property will no longer be eligible once it reaches the limit.

Tim Borlase stands on the porch of his cottage in Pointe-du-Chêne. Despite behind raised to higher land and set back from the ocean, flood waters during Fiona reached the front door. (Alexandre Silberman/CBC)

The program is not available to seasonal properties and most homes in the area are not eligible for private flood insurance.

Building higher

New homes going up on the coast are noticeably higher, built on raised parcels of land. Existing cottages are also being raised.

Those living directly on the shoreline are installing armour rock or repairing and creating seawalls, reinforced with metal rods, rocks and wooden structures.

Borlase raised his nearly 100-year-old cottage after a storm flooded the first floor in 2000. But he said people in the community are now looking for other solutions that will buy more time.

"I think most people have come to the realization that there's not a lot of sense in spending money in raising up more, unless it's going to be significant. Because this is going to continue to happen," he said.

"There's nowhere to move here, there's no green space left. So to be told to move back, there's nowhere to move back to."

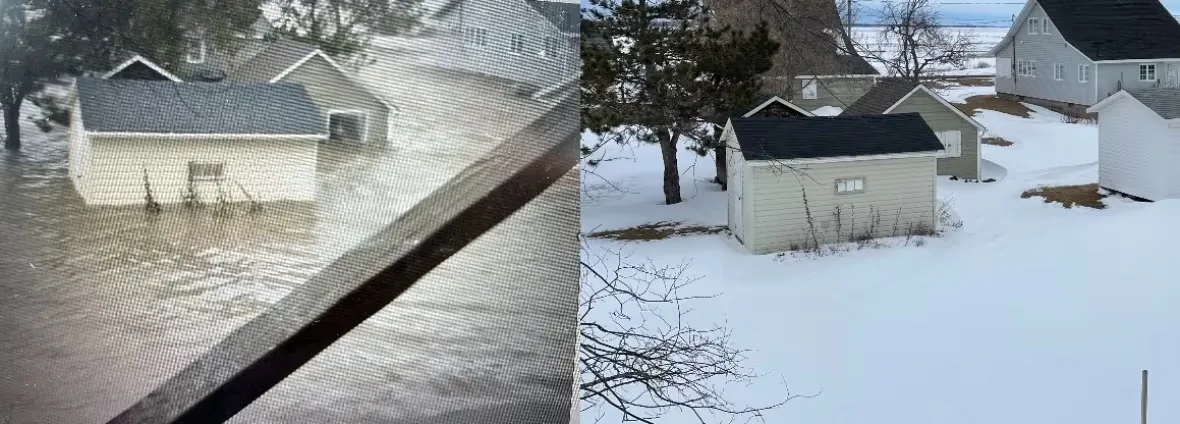

The view out Tim Borlase's upstairs window during post-tropical storm Fiona on Sept. 24, 2022, and on March 10, 2023. Storm surge came about an inch from entering the cottage. (Submitted by Tim Borlase / Alexandre Silberman/CBC)

Disappearing dunes

On New Brunswick's southeast coast, projections show the ocean will continue to rise even higher during future storms. During extreme events, sea level is expected to be more than a metre higher in about 70 years, according to a 2020 report. That would leave many homes flooded and surrounded by water.

Natural protections have also taken a beating after recent storms. Fiona eroded large sections of dunes, drastically changing the landscape and view of the ocean.

A local group of residents are now trying to better protect Pointe-du-Chêne against flooding. The Red Dot Association, an environmental group that has drawn attention to water quality and development issues, has applied for provincial funding to hire an engineer to study possible berms and floodgates.

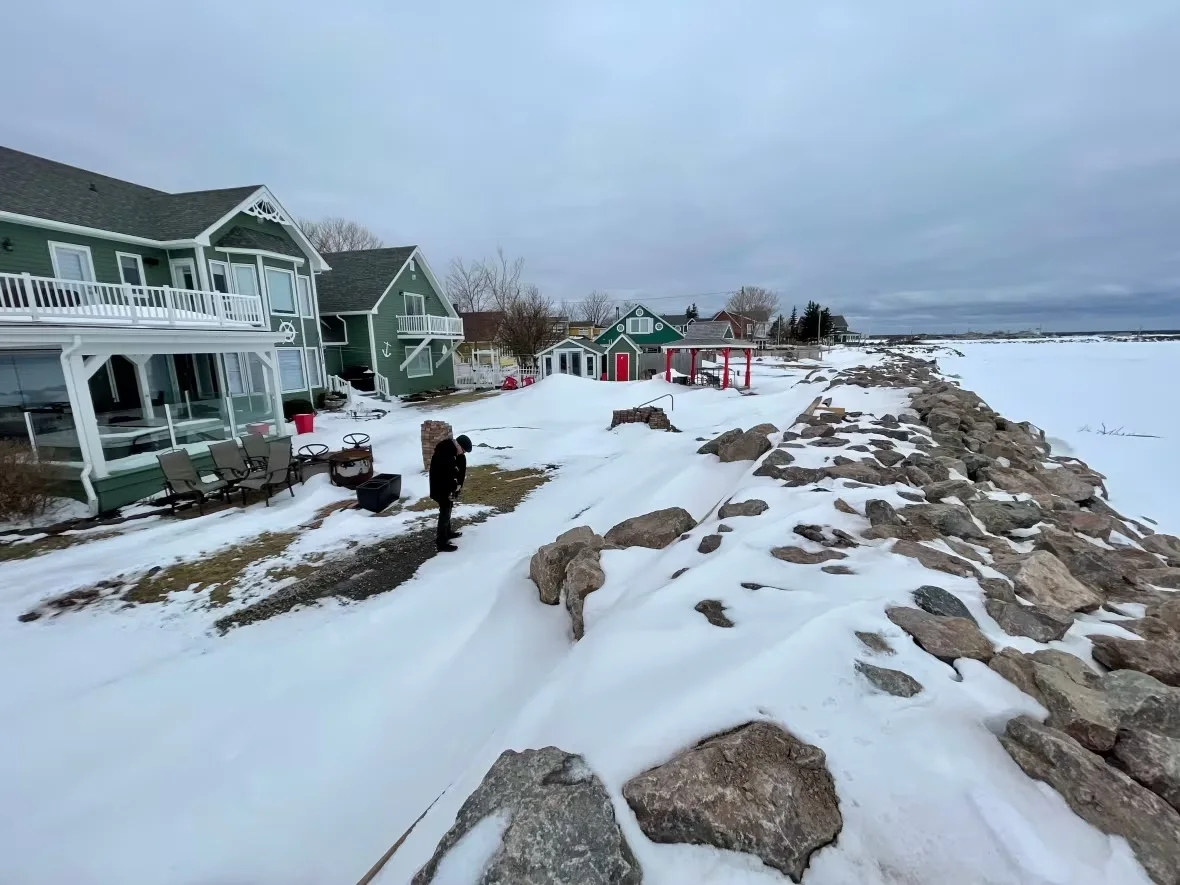

The seawall in front of this waterfront home, which was heavily damaged by Fiona, has been rebuilt and reinforced. (Alexandre Silberman/CBC)

The organization is calling for protection of dunes, grasses, marshes and wetlands. Members also want to see a tidal creek, which backs up during storms, get dredged.

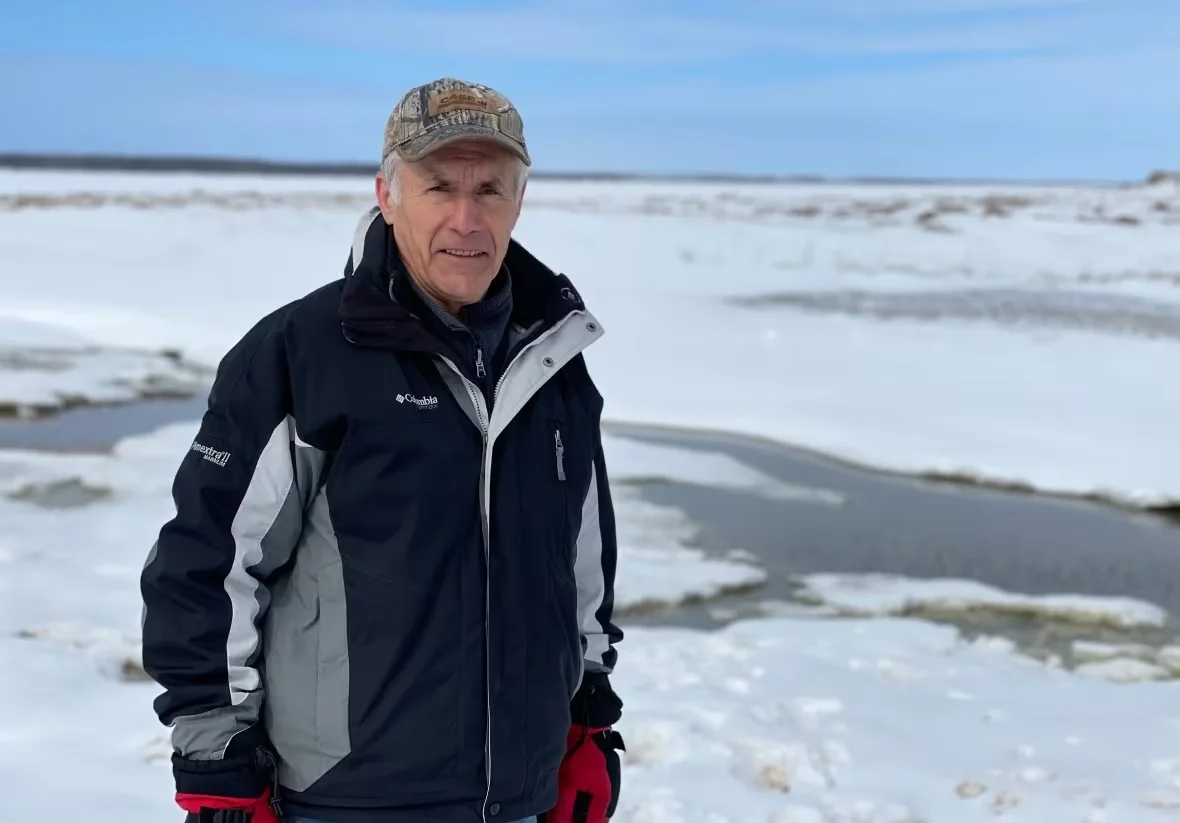

Arthur Melanson, a resident and member of a local environmental group, stands on the shoreline of his community. Behind him are the remnants of once-prominent sand dunes that protected against storm surge. (Alexandre Silberman/CBC)

Arthur Melanson, a resident and member of the Red Dot Association, said solutions are urgently needed beyond the efforts of individual property owners. Well water contamination is a concern with each storm, he said.

"We keep raising the houses but the infrastructure doesn't raise, like the road structure stays there, the sewage system stays there," he said.

Long-term solutions: build high or leave

Next to Pointe-du-Chêne's flood-prone St. John Street, which leads to the ocean, once-towering dunes have nearly disappeared. Without that protection, residents are calling for dune restoration. But many also want a seawall to hold back the waves from crashing onto the road.

Jeff Ollerhead, a coastal scientist and professor at Mount Allison University, said putting in a large barrier would permanently alter the shoreline and simply buy time.

Jeff Ollerhead is a coastal scientist and professor at Mount Allison University in Sackville. He said long-term solutions for erosion are to build higher and away from the shore. (Alexandre Silberman/CBC)

"I suppose you could build a 10-metre-high concrete wall and then that would buy you a lot of time. But then your shoreline would be that. It would be a 10-metre-high concrete wall," he said.

Ollerhead said replenishing the dunes, which is done at nearby Parlee Beach, is also a short-term buffer to erosion.

"As sea level rises, the only long-term solution is either move back or move up, or a combination of the two."

WATCH: Storm Hunter describes how Fiona left an eerie trail of destruction

Thumbnail courtesy of Alexandre Silberman/CBC.

The story, written by Alexandre Silberman, was originally published for CBC News.